Test drive: Mercedes-Benz EQC

Overview

If you’ve ever been in one of Mercedes many SUVs, the EQC will feel very like them, except with silent electric power. Because that’s what it is. For its first mainstream EV, Mercedes hasn’t reinvented the car. It has simply electrified a car. Specifically, the GLC.

Take out the combustion engine, exhaust and fuel tank, and the transmission. Insert two drive motors, one in front and one behind, and an underfloor battery. That’s the basic concept anyway, but of course thousands of details have changed, and there’s a new visual skin for the exterior and interior.

This means that both outside and inside, the EQC has very similar proportions to the GLC. It doesn’t have a spacey cab-forward design or a lightweight aluminium bodyshell. You don’t have to get used to it, and you won’t look like you’re driving around in a science experiment.

It might seem timid for Mercedes to have adapted an existing platform rather than scratch-build a new one, but at least they have sweated the details on the body, motors, thermal systems and electronics. The aims – successfully met in our first experience – were silence, efficiency and safety.

Among the first wave of posh electric crossovers, it’s quite small. The Jaguar I-Pace is similar in footprint but has a significantly longer wheelbase to improve cabin room. The Audi e-tron is bigger, and the Tesla Model X far bigger. And yet the Mercedes is the heaviest of the lot, at two-and-a-half tonnes.

Here’s why. The EQC has the same suspension and most of the underbody as the GLC. To make sure it behaves in the same protective way in a crash, it even has steel-tube replicas of the combustion car’s engine block and gearbox housing, except here they mostly enclose fresh air rather than pistons and gears. So you don’t get the airy cabin or flat floor of a Tesla or Jaguar.

The EQC’s chief engineer gladly admits that because it’s thus adapted, it’s 150kg heavier than it would be if entirely bespoke. He claims weight doesn’t greatly affect range because you can regenerate more from a heavy car – here it’s up to 240bhp feeding back to the battery. Instead, what matters is low drag, down to Cd 0.28.

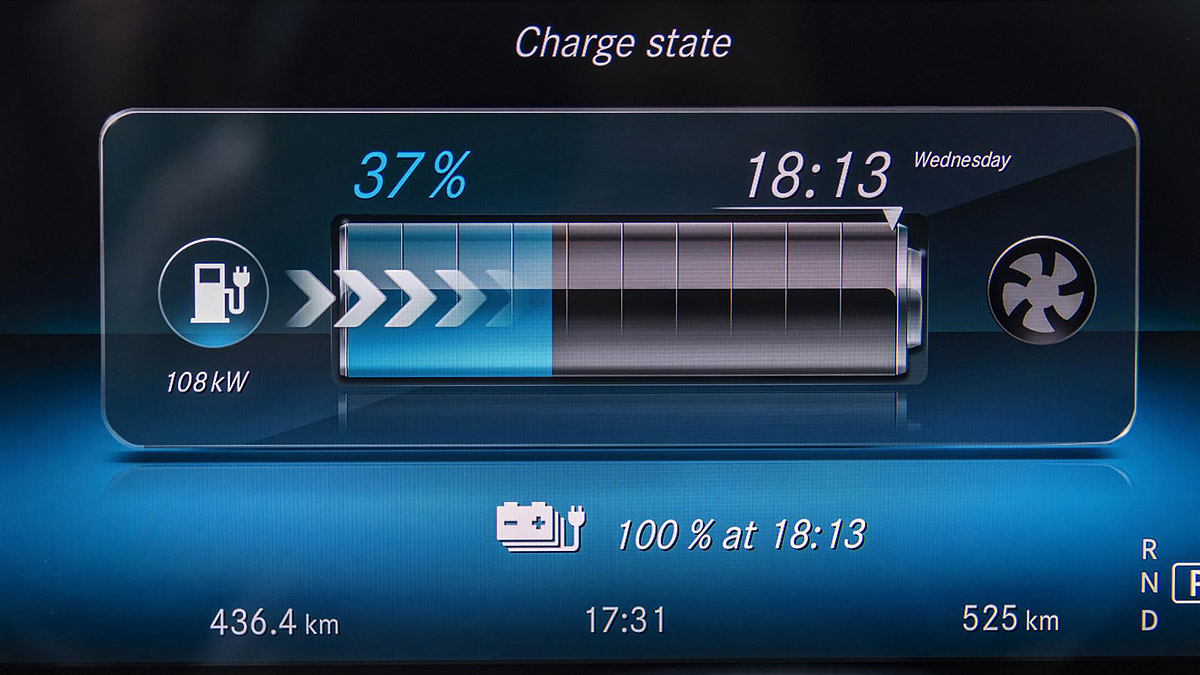

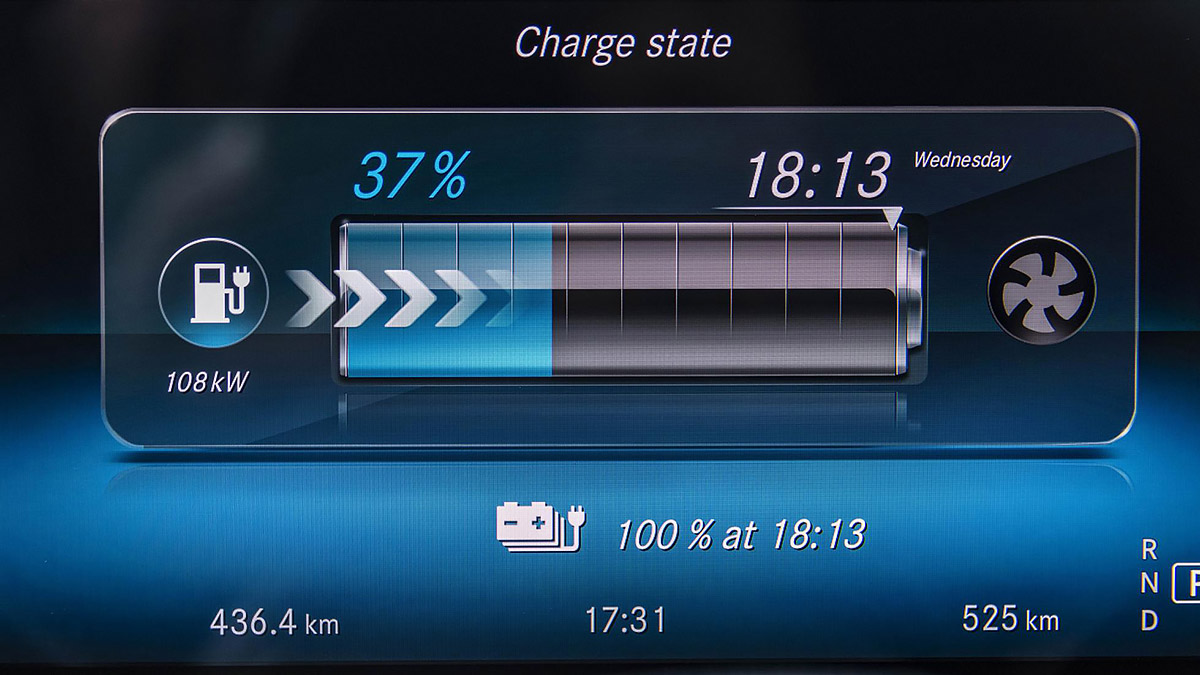

Just as well, since the battery doesn’t have a huge capacity, at 80kWh gross. Mercedes are absolutely the safety people, so they’ve made the EQC’s battery narrower than rivals. It doesn’t spread right out to the sills but instead has about 10cm of extra impact-absorbing structure either side. The range is 231 to 259 miles WLTP, depending on wheels (some low-drag ones are available) and running boards (which actually improve matters).

Driving

Awesome refinement is its main appeal. Low-speed motor whine is absent, and high-speed tyre and suspension noise are also brilliantly suppressed. It’s fabulously serene. The ride isn’t pillow-soft, so you know there’s a bumpy road beneath. But it does filter out secondary harshness really nicely. So it’s fabulously serene.

But it’s a two-and-a-half tonne car and feels it, especially since the damping – which isn’t adaptive – is soft. Chuck it around bends and it rolls and pitches and generally comes over all calm-down-madam on you. Just ease off and stretch the range.

Acceleration is really solid if you ask, thanks to front and rear motors of 204bhp each. The 0-62mph number is 5.1 seconds, and it’ll get close to that even in poor grip because the traction control is so good.

But the performance impression comes more from the motors’ instant wits than it does from the actual sustained rate of acceleration, which is tethered by the mass. Also, like many EVs, its acceleration from above 60mph or so would be beaten by a combustion car in kickdown mode. There’s no kickdown here: it’s single-speed.

You can set the EQC’s regenerative braking at several levels. The cleverest is the efficiency-chasing ‘auto’ setting. This uses the car’s camera and radar sensors, and navigation data, to build up a picture of what’s ahead. The speed of the car you’re following, the speed limits applying and upcoming, hills and valleys and junctions and bends – they’re all taken into account. Dashboard symbols encourage you to lift early and coast, and regeneration cuts in only when needed.

This can feel odd, because the car doesn’t consistently behave according to your foot position. But it eventually encourages you into range-stretching behaviour that doesn’t actually lose you much time in normal traffic.

On the inside

The cabin is normal Mercedes, except for some progressive-looking rubberised fabric stuff on the dash and seats (recycled, natch). The colours are livelier too, with signature copper vents and so on.

The front seats are high up enough to satisfy the SUV thing. But the back ones suffer versus rival EVs because the wheelbase is comparatively short. And the centre tunnel remains, despite the prop shaft and exhaust having been evicted. The boot’s not bad but again, unlike rivals, there’s no frunk.

Facing you is the company’s vast and occasionally annoying twin-screen edifice. It’s controlled in any number of ways, including over-twitchy steering wheel touchpads.

A brilliant head-up display comes with the expensive trim levels. And the silence lets you enjoy the awesome Burmester hifi.

Verdict

Mercedes has been cautious in its first electric car. (Well, first except for the electric Smarts, electric B-Class and electric SLS.) By using an adapted GLC platform there aren’t the gains in revolutionary style or cabin space you’d hope for. It’s not at all sporty to drive either.

But the detail of its refined drivetrain and chassis makes it a relaxing car to drive or ride in. And Mercedes has done all it can to ease the transition to finding energy from power points not petrol stations.