Mazda 787B remembered 30 years after its triumph in Le Mans 1991

Really, the movie script writes itself. The plucky outsider, doing things their own way and with a fraction of the money the big boys have. The elite, who dominate the sport and divide the spoils between them. A sage from a bygone era of the sport who guides the outsider to glory in a last-ditch, do-or-die attempt. The hero who pushes themselves beyond the limit to make their dream a reality. Sounds too good to be true, and yet every part of it is. It’s the very real story of the Mazda 787B, and its one-in-a-million victory at Le Mans, 30 years ago.

The 59th running of the 24 Hours of Le Mans really was Mazda’s last opportunity to prove itself, and the engine it had chosen to champion where no one else would. Rule changes for the following year meant that rotary engines (and many more besides) were out as of 1992, and engines that marched in step with Formula One would be the norm.

Mazda had been extolling the virtues of rotary power in Group C since 1983, and in racing since the Mazda Cosmo placed fourth (behind two 911s and a Fulvia HF) in the 1968 running of the 84 Hours of Nurburgring. Yes, 84 Hours, not 24. So, after 23 years of rotary-powered racing, this was the revolutionary engine’s last shot on the world stage. And decades of honing and refining meant the world’s best-ever rotary engine would be the one to take it.

In the early days of Group C, Mazda ran roughly the same 13B rotary that powered its road-going cars and GT racers. But extending its capabilities and solving its shortcomings over the best part of a decade meant that, by the time the 787B turned a wheel at Circuit de la Sarthe, its engine was a technological marvel. Four rotors, with three sparks plugs each. Peripheral intake ports. Ceramic apex seals. Continuously variable, telescopic intake runners that smoothly slid from long to short and back again, ensuring mid-range torque – not a quality generally associated with rotary engines – as well as peak power. And if torque is one thing a rotary engine isn’t exactly famous for, fuel economy is the other. And yet, that’s a key part of the 787B’s victory.

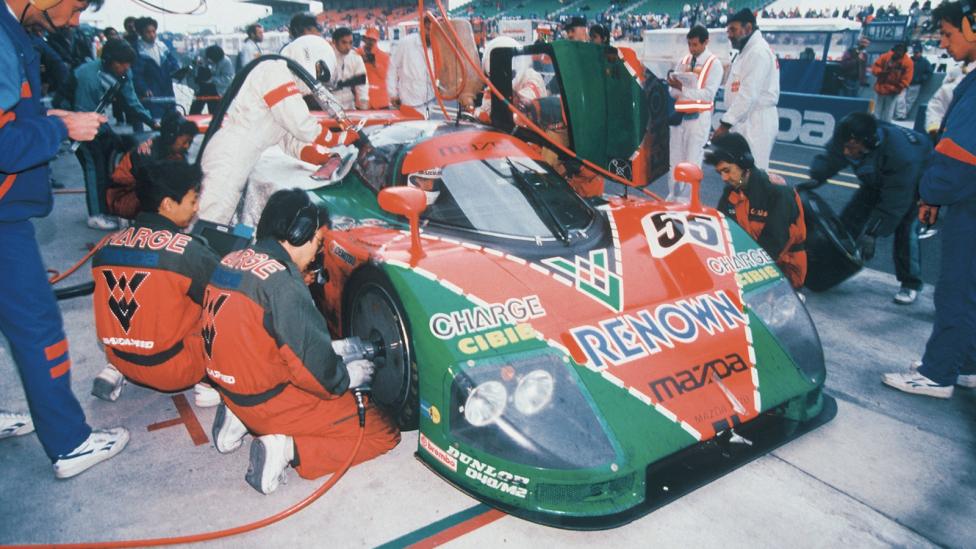

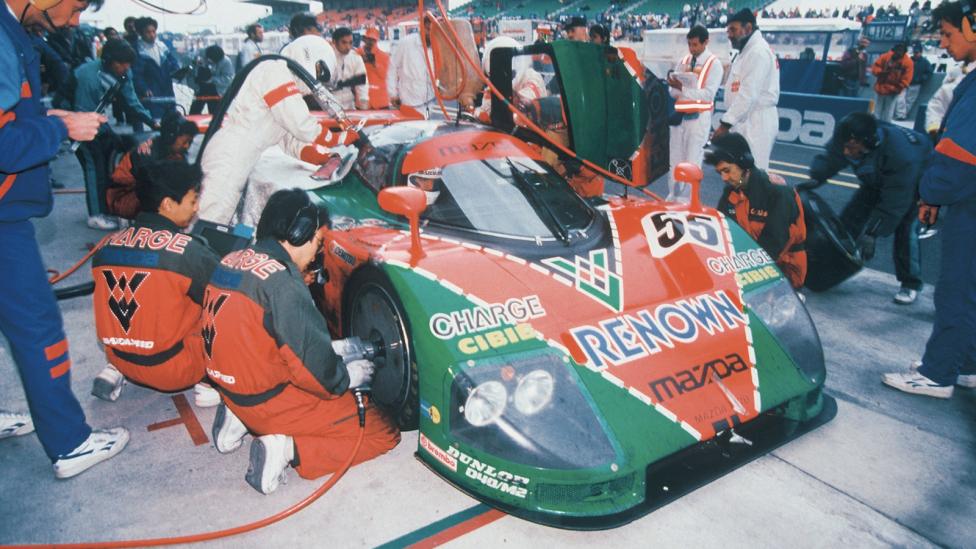

After a hugely disappointing debut for the 787 in 1990, Mazda did some pretty serious Monday-morning quarterbacking and came up with a list of areas of improvement for the 787B, which boiled down to roughly what any racer wants more of from any car they’re racing: reliability, fuel economy, suitability to the circuit, acceleration, cornering speed, driver comfort and so on. But then Mazda’s engineers actually went and did it.

Mazda’s chief of product development demanded another 100bhp over the 630bhp in the 787, as well as a 10 to 15 per cent bump in fuel economy. Thanks to a huge overhaul of the engine, which featured more than 80 improvements – including those telescopic intake runners and three spark plugs per rotor – Mazda’s engineers managed another 70bhp in endurance-race trim (and reportedly as much as 900bhp if properly uncorked), as well as what might be the most linear torque curve in racing. Foot hard down anywhere from 6,000rpm to the 9,000rpm redline meant at least 95 per cent of peak torque. In real terms, that meant the 787B could stay at basically full shove around the entire circuit.

But to nail that economy target, it meant the drivers had to exercise incredible restraint and maturity – in the slow corners, they needed to be smooth and gentle on the accelerator, saving full throttle for the high-speed sections. Helpfully, Mazda had hired six-time Le Mans winner Jacky Ickx as a consultant team manager / coach / endurance racing guru. And so, rather than letting the red mist descend, Johnny Herbert, Volker Weidler and Bertrand Gachot instead competed against each other in practice to see who could be the fastest while still hitting the required economy figures.

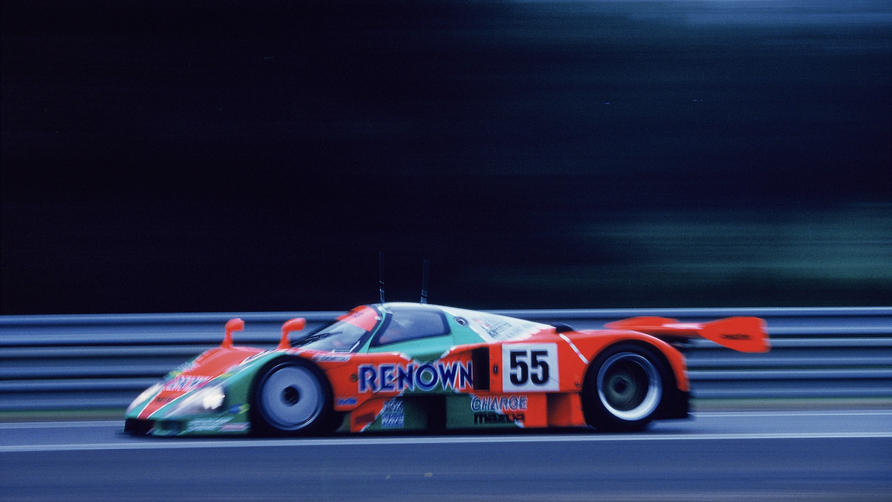

But if we’re going to talk about the R26B engine, we’re going to have to talk about the noise. A wailing, soaring sound, with a timbre more like a MotoGP racer or V12-engined F1 car than anything lining up on the grid at Le Mans. A sound perhaps best described as a banshee riding a Jericho trumpet. Or perhaps better looked up on YouTube. It was a sound that endeared the 787B to spectators then and continues to raise eyebrows and neck hair whenever it’s out on the track.

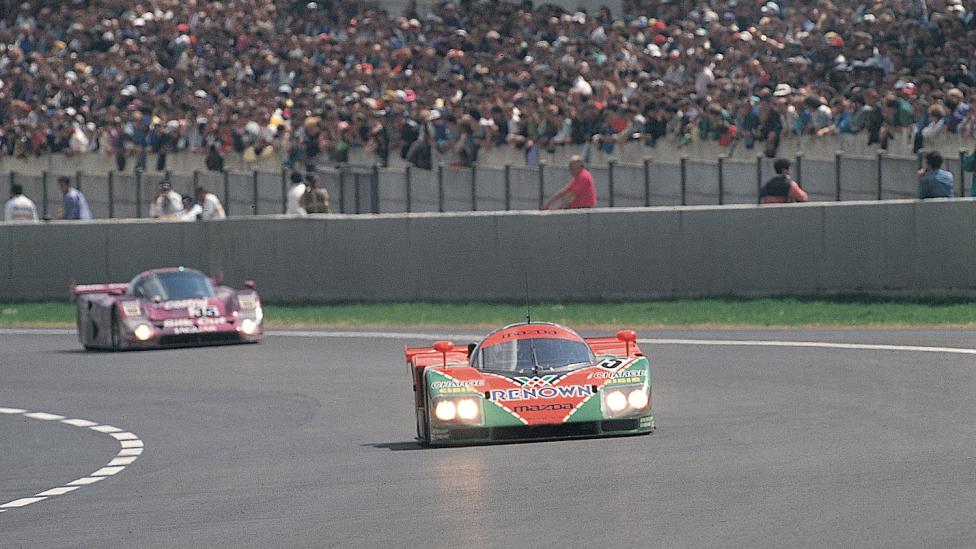

The Number 55 Mazda started from 19th on the grid despite qualifying 12th fastest, due to the FIA holding the first 10 places open for cars that fit its preferred formula. But the rules likely helped Mazda more than they hindered. Both the Tom Walkinshaw Racing Jags, which had won in 1990, and the perennially popular Porsche 962, which had won in 1987, were lumped with hundreds of kilos of ballast as a punishment for being old-school Group C cars, as opposed to the new standard the FIA was pushing for.

So the Jags and Porsches were off the pace and thirstier to boot. Andy Wallace (yeah, that Andy Wallace) and his cohorts at Jaguar were instructed to short-shift and coast into corners to save fuel, with the Jags eventually nabbing second, third and fourth places. As for the Porsches, not even Derek Bell and Hans Stuck could get the 962 higher than seventh overall.

Cannily, Mazda’s team boss Takayoshi Ohashi petitioned for an exemption to the weight penalty. Clearly, no one expected Mazda to be that much of a threat, because the exemption was granted, and the 787B took to the track without any ballast, weighing just 830kg.

Regardless, the Sauber Mercedes were tipped to win. They had the speed, the reliability, the depth of experience and the depth of budget. They also had drivers like Jochen Mass, who’d won Le Mans in 1989. Oh, and Michael Schumacher. But Schumacher’s incredible pace – knocking five seconds off the lap record at one point – was stymied when his Mercedes retired with gearbox issues. Then Stanley Dickens (co-winner in 1989) ran over debris, damaging the floor and crankshaft damper in his Merc, and was out too. The last remaining Mercedes – which had led from just six hours in – fell victim to a broken bracket that rendered the water pump useless and overheated the engine.

And here we find the final scenes of the movie. With the supposedly shoo-in Mercedes cars dropping like flies, Johnny Herbert found himself in the lead. Jacky Ickx got on the comms and asked Herbert if he wouldn’t mind doing an extra stint to ensure the win. Herbert agreed, despite a few impediments. Firstly, he’d exhausted his water supply in the first stint and was severely dehydrated. Secondly, he was racing with an injury doctors had described as career-ending just a few years earlier.

As Herbert described the injury to Motorsport a while back: “The left foot was the one that was hanging off, so they sewed it back on. The right one just got smashed, dislocated at the ankle, the big toe got sliced off, it all got very hammered.” Needless to say, it caused horrific damage, lasting pain and permanent loss of function. “The left ankle joint got broken, too, so they put that back together, but I haven’t really got any movement in that one,” he said. Herbert amazingly not only found his way back into the driver’s seat, but found proper pace once he got there.

The same determination that had taken Herbert from a hospital bed to the peak of motorsport carried him and the 787B across the finish line, two laps ahead of the second-placed Jaguar. The racing rotary’s swan song was a 9,000rpm wail, and its parting gift was victory in one of motorsport’s highest echelons. Herbert wouldn’t make the podium to celebrate, however – he collapsed shortly after getting out of the car and needed to be carried to the medical centre for fluids and a check-up. But you’d better believe he made the after-party. Roll credits.