Let’s begin with the reassuring words of Jim Glickenhaus, owner of the world’s wedgiest Ferrari, minutes before we chase him up the road in our hired hatchback somewhere south of Maranello. How much is his one-of-a-kind, virtually undriven Seventies concept car worth, exactly?

“You tell me,” he says with a helping of New York attitude. “It’s been in the Louvre. It was displayed in a glass box in Florence for a month. What’s the most damage we could do? Worst case, it would probably cost two million dollars to put right. Not, like, 10 million.”

Not many people could make a multi-million-dollar accident sound like a cut-price crash, but then not many people are like Jim Glickenhaus. Almost as soon as the words leave his mouth, he’s off, exhaust smoke blackening the pearly white tail of his extra-terrestrial wedge as we try to keep up, photographer Mark shooting valiantly through the passenger window.

Jim has other things to worry about than our pictures, like not smashing up his new plaything on its maiden voyage. Because other than a run around the block and a trip across the Pebble Beach concours lawn, this is the first time he’s taken it into the wild since he bought it five years ago. It’s the first time anyone has driven it properly since it was made, way back in 1970. Even then, it was only ever pushed onto exhibition stands, or free-wheeled down slopes for videos.

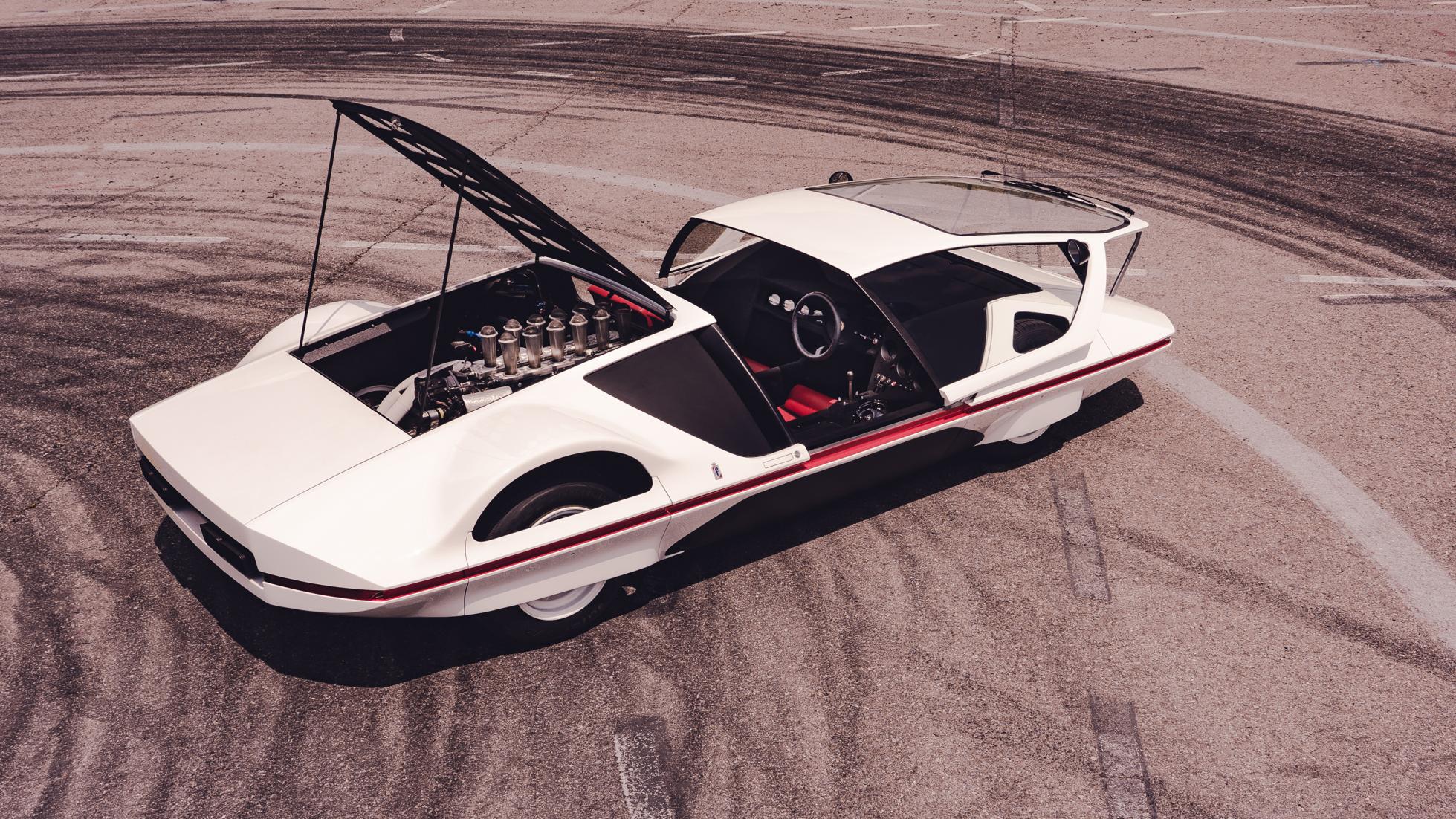

It’s called the Modulo, and despite being nearly 50 years old, it could have just beamed down from a passing mothership. Designed as a concept car by Pininfarina, it was first shown at the 1970 Turin Auto Show – wearing its original tuxedo-black paintjob – before being sprayed white and taken on a world tour that proved so popular it lasted for almost 14 years.

But here’s the thing. Whereas most concept cars are merely a shell to showcase some designer’s sketchy handiwork, the Modulo’s spaceship body rests on the spaceframe chassis of an actual Ferrari 512S – the endurance racer with a 5.0-litre V12, good for more than 200mph (322kph) along the Mulsanne Straight. It’s Sixties speed meets sci-fi styling, a proper Le Mans warrior from the future. But it wasn’t always that way.

Exhaust smoke blackens the pearly white tail of the extra-terrestrial wedge as we try to keep up

Before giving the donor car to Pininfarina, Ferrari removed its guts, leaving only the engine and gearbox casings to give the illusion of a working powerplant, glimpsed through that cheese-grater rear deck. It was only ever to be a show car, so it wouldn’t need to run. And for 44 years that’s how it remained, until 2014 when Glickenhaus bought the Modulo directly from Pininfarina and vowed to bring it to life.

But Jim being Jim, that wasn’t enough. Not only would it run – it would have number plates, like all the racing exotica in his collection. “The one thing I insist on is making cars usable,” he says. “If they don’t drive, they don’t exist.” Because if he wants to ride to work in an old Le Mans car with Buck Rogers bodywork, then why the hell not?

Of course, all of this requires cash. Barrels of it. Not a problem for Jim – son of a Wall Street wolf, he made his own millions as a B-movie mogul, built one of the world’s wildest car collections, started a successful racing team and now makes buyable, road-going versions of his endurance racers under the banner of Scuderia Cameron Glickenhaus, or SCG.

Even so, project Modulo was no easy endeavour, and here’s why. Ferrari made 25 examples of the 512S – the number required for homologation – plus a spare or two. It wasn’t a bad racing car at all. The trouble was, it was up against the Porsche 917, and we all know how that played out. Then the world sports-car regs switched to smaller engines. The upshot: Ferrari couldn’t use or flog the 512S, so the cars became surplus stock. Some were turned into 612 Can Am spec, and it’s one of those which Enzo gave to Pininfarina.

At around the same time, a young designer at Pininfarina, Paulo Martin, had been moonlighting on a wedgy concept car when he should have been concentrating on the Rolls-Royce Camargue. While this may explain a thing or two about the bloaty Camargue, it did mean that when the gifted 512S came along, Pininfarina had a ready-made design up its sleeve. The Modulo was born.

Seeing it up close now, it’s not quite the classic doorstop it first appears to be. There’s a softness to the edges, its hips are rounded, the windows curve slightly, the wraparound waistband tapers. But there’s drama: the entire glasshouse slides forwards over the car’s nose like a fighter jet canopy, supported by struts which slide through slots in the nose. And the whole thing is barely taller than its own tyres – ten quid says it could scoot under an 18-wheeler and come out the other side, Smokey and the Bandit-style.

Getting to the chaise-longue seats involves a bum-shuffle over wide sills which are really 40-litre fuel tanks positioned each side like saddle bags. Once in, you survey the geometric dash – upholstered with several square metres of dark carpet – from down low. Each side of the cockpit are hemispherical ‘control domes’, modelled on a couple of stolen bowling balls smuggled by Martin on his Vespa, who must have rocked the pregnant hunchback look as he rode.

“Paulo takes 100 per cent credit for the Modulo,” says Jim. “He made it his life, travelling around the world with it. But for me, it was actually Syd Mead who first imagined this car.” Sure enough, Mead – the futurist illustrator and visual brains behind Blade Runner, Aliens and Tron – had pictured an uncannily similar Modulo-like shape almost 10 years earlier, in his 1961 drawings for US Steel.

Whatever the inspiration, the Modulo inflamed the War of the Wedges that would shape supercars for the next couple of decades. The Stratos Zero concept was displayed just a few stands away from the Modulo at the 1970 Turin show. The radical Porsche Tapiro was there too. And the trickle-down to production cars was rapid – it wasn’t long before Ferrari launched the 512BB, followed by Lamborghini with the Countach and Lotus with the Esprit.

Why, then, would Pininfarina part with such an important part of motoring history? The reasons are a little murky, but the gist – according to Jim, pictured – is this. In 2014, the company was in financial trouble, and in desperate need of a cash boost. If it went under, there was a chance that the Modulo could have been seized by the Italian state, like some sort of national treasure.

Jim has history with Pininfarina – most famously collaborating on the Enzo-based P4/5 and p*ssing off Ferrari in the process. So he put up the money. All $2.3m, on one condition: the Modulo was part of the deal. He wired the cash and flew to Turin overnight. “I called Sal [Jim’s long-time mechanic] and told him to bring a trailer,” says Jim. “The PR lady let us in and we took the car. I was even ready to air freight it back to New York that night, if the authorities played games.”

With the car safely in his possession, Jim could get to work. But how do you go about bringing a vintage, disembowelled endurance racer to life? The answer is on a dusty backstreet a few miles from Enzo Ferrari’s birthplace, in the renowned workshop of Sport Auto Modena – founded as an official Ferrari service centre in 1967 by Gianni Diena and Aldo Silingardi, who until then had worked for Enzo. Unable – or unwilling – to pay them properly, the old man instead gave them parts, which they stored and catalogued. These days it’s run by their sons, Giordano and Andrea, who use that same archive to restore cars with new-old parts.

Their first job was to convert the Modulo from 612 Can Am spec back to its original 512 set-up. “The difference was simply the liners in the pistons – it’s the same block,” says Jim. “Then it was on to the rest. What we didn’t have, we could reverse-engineer and build ourselves. My brief to these guys was to make the car drivable, keep it as original as possible, but most of all, make it safe.”

Not everyone’s happy. Jim is regularly trolled in forums saying he’s corrupted the car.

On went a pair of wipers and wing mirrors, plus a set of road tyres specially made by Michelin. The team also put in cooling fans, fed by bat-wing air scoops which open out to reveal fuel filler caps, one each side (it runs on regular pump petrol). They also fitted a ventilation system to force fresh air into the cockpit, “otherwise you’ll carbon monoxide yourself to death,” says Jim.

But not everyone was happy. Jim is regularly trolled in forums by unsociable sorts who say he’s corrupted the car, that it’s no longer original, that it should remain a static work of art. Some said it would never drive properly, that the wheel spats stop it from steering. Bullsh*t, says Jim. “OK, we changed the rack, so the car steers – I mean, I wouldn’t wanna get stuck in downtown Manhattan, but it’s certainly drivable.”

On the road near Maranello, he proves his point. The big-chested V12 clears its throat, the transmission whirs and the Modulo swishes through the corners. It deals with roadworks and potholes and village bottlenecks. We even manage to get a few pictures. And then, just as we’re planning to swap places – Jim was actually prepared to let me drive it – the alternator belt snaps.

“That’s real racecars for you,” says Jim. “They come off the transporter, they go a lap, you cut ’em, you change ’em, you fix ’em.” And as the traffic thickens and dark clouds gather, it’s probably just as well. Jim might be good for the two million, but I most certainly am not.