Bloodhound SSC: the full story

It’s important to remember there is only one. This isn’t a prototype. It’s Bloodhound. The first, last and only. Crash it and the rebuild costs would likely put the project out of action permanently. So only one person will ever drive it: Andy Green. But that’s alright – he’s the one and only man on the planet who has previous when it comes to supersonic Land Speed Record cars. No man is better suited to the task than the current Land Speed Record holder. Doesn’t hurt that he flies fast jets for the RAF when he’s not doing this.

It’s debrief at the end of the day at Newquay Airport. We’re all standing in a leaky portacabin. Pallets laid on the ground outside stop you getting your feet wet as you walk here from the massive cold war hanger that’s Bloodhound’s current garage. Andy Green is telling everyone how testing went from his point of view: “We knew that reheat takes about a second to shut down, what the book doesn’t record is how much thrust it generates in that second. The answer, it turns out, is a lot.”

Reheat: lighting up the afterburners to you or me. Augmented thrust if you want to get properly technical about it. One of the engineers asks how long he’d been in reheat. “About three seconds. In my defence you will see the throttle was idle and I was hard on the brakes as the car continues to accelerate. And then I was fully focused on the braking. I think I may have said ‘we’re in trouble’”.

Bloodhound, I should add at this point, is still in one piece. But the fact it was still accelerating when Andy was hard on the stoppers must have been unnerving to say the least – it’s a reminder that this is a project aiming into the unknown. 1,000mph in a wheeled vehicle. If it succeeds it’ll also break the speed record for low level flight. Are they taking risks? No, they’re analysing and managing risk. Today was simply the next step along the path. They’d started with static tests, Bloodhound lashed to the ground and spitting flame and fury, then slow speed runs up to 50mph, 75mph, 100mph. Today was the day they lit the afterburner for the first time. Turns out it’s quite effective.

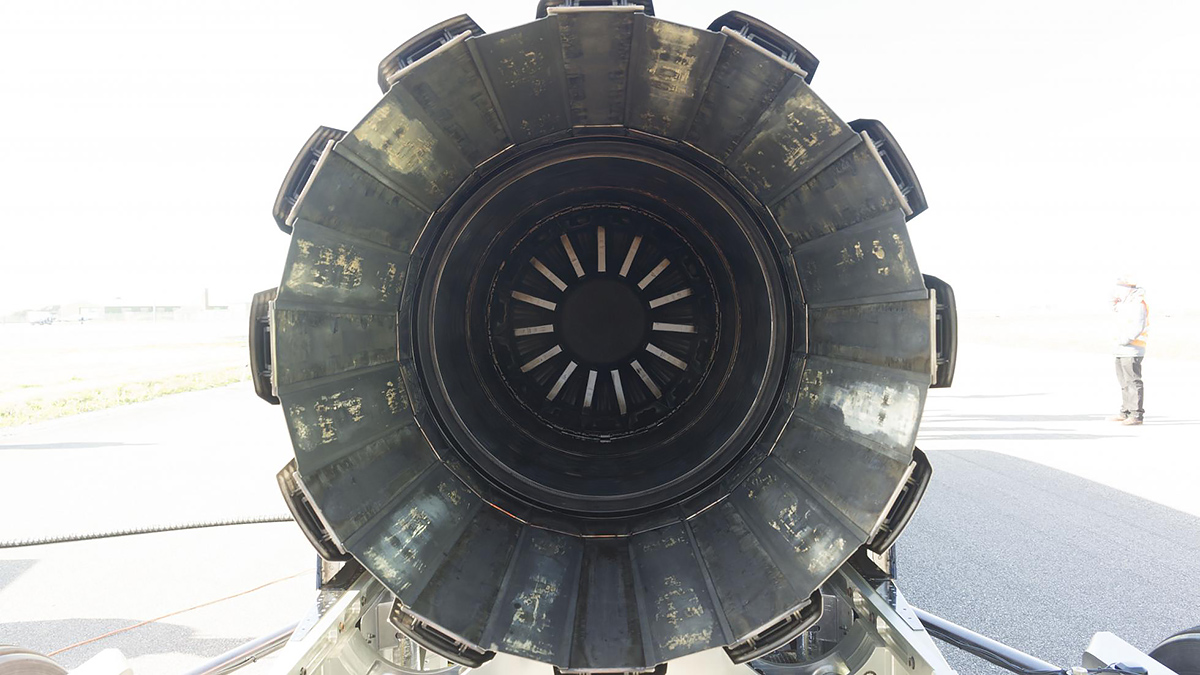

Because they’re forging a path, because no-one’s designed a 1,000mph car before, the design software, the maths and CAD/CFD systems have to grind to a halt somewhere. They can’t accurately predict everything that’s going to happen. One of the main things they needed to find out at this first dynamic test was how good the Rolls-Royce EJ200 jet engine is at sucking in vast quantities of air at low speeds. The answer is way better than expected.

This not only vindicates Bloodhound’s design, especially the complex 3D shaping of the intake above the cockpit, but means it accelerates with alacrity. Added to that is the fact that even after pulling back to neutral throttle, a fair amount of fuel is still left in the system to be injected into jet and exhaust. At this stage Bloodhound is piling on around 30mph per second, so things could get decidedly exciting quite quickly on a runway measuring only 1.7 miles long. Which is why you need Andy Green at the helm. I’ve never met a man more in control of himself.

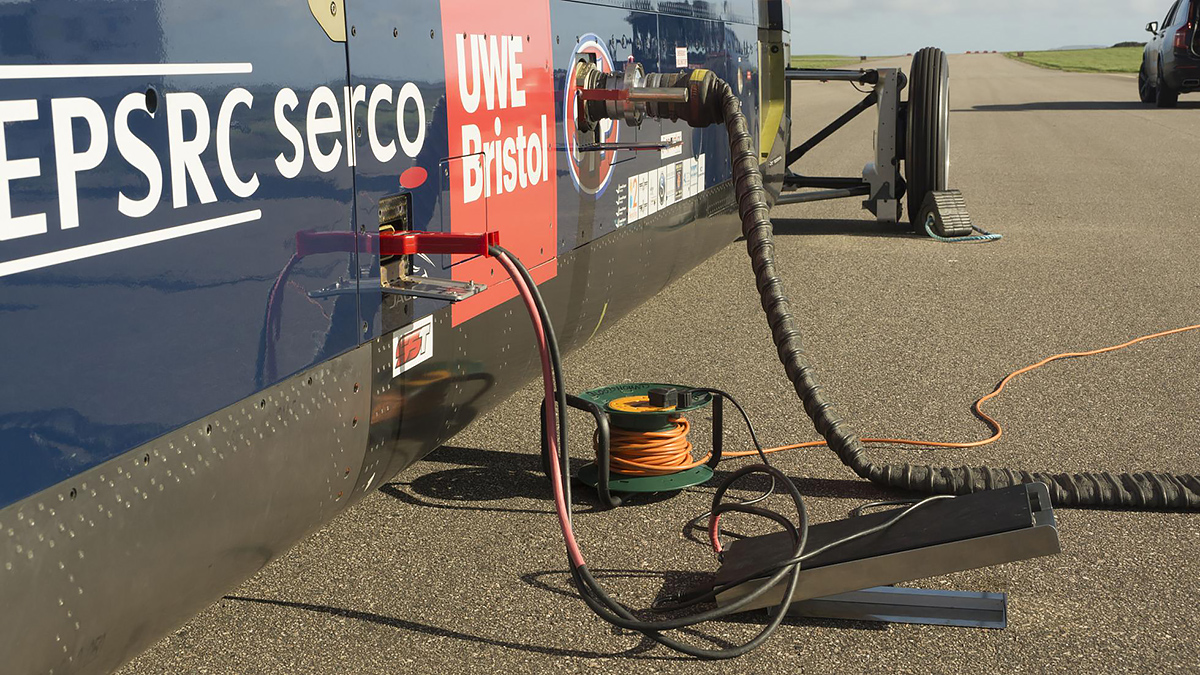

Bloodhound is exceeding expectations. Because of this, spirits are high. When I arrive down there in the morning, the mood is buoyant. People are whistling while they work. Bloodhound is parked (parked!) calmly in the middle of a hanger illuminated by gantry lights. There’s no frantic running, no panicky spannering going on. Someone asks who wants a brew, their voice echoing around the chamber, a neat ‘to do’ list is written up on a white board. The first thing chief engineer Mark Chapman wants to show me is nothing to do with Bloodhound. He leads me to the back of the hanger and slides open a second vast set of iron doors. Behind them is a curving concrete blast tunnel: “This used to be a hot start hanger in the cold war. They could fire up the jets in the hanger and have them in the air in about three minutes”.

I’m not sure the cold war ever had a machine as powerful as Bloodhound though. The combined thrust of the EJ200 jet and Nammo triple rocket pack is equivalent to roughly 135,000bhp. 0-1000mph will take less than a minute pulling a near constant 1.5g and, from a standing start, covering almost six miles in that time.

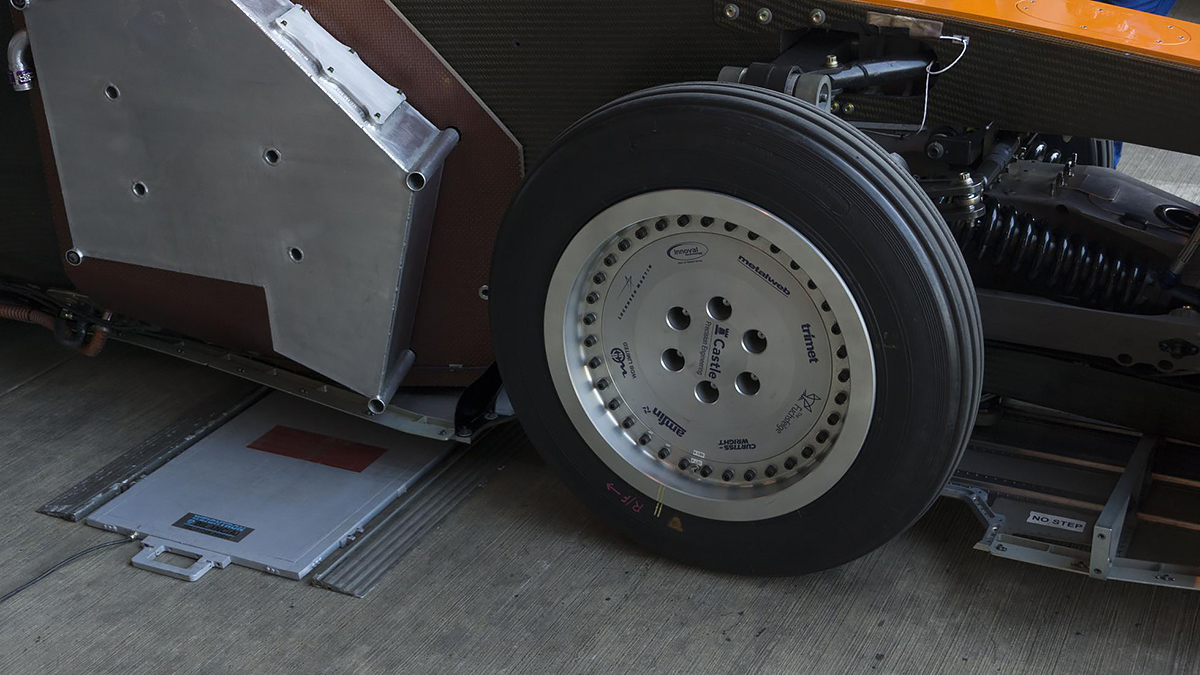

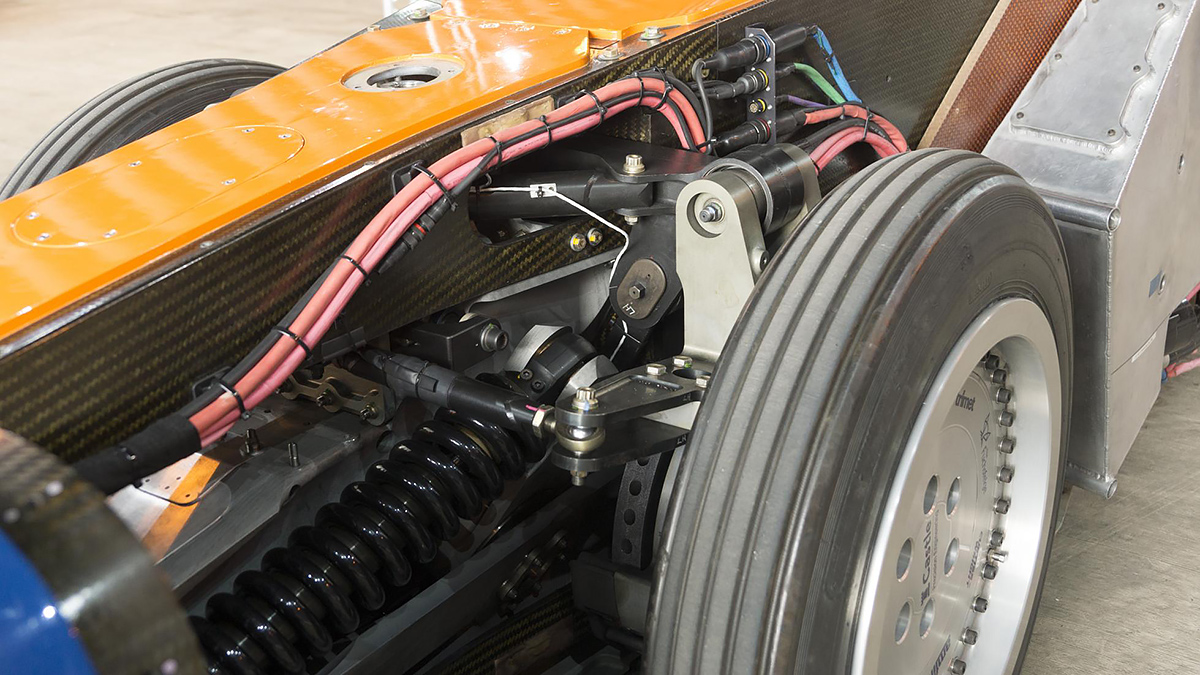

Just not in the trim it’s in now. The fin, replete with the names of private sponsors like you and me, won’t be fitted until next week. There are no fairings on the rear wheels, nor bodywork over the fronts. Why? Because the rubber runway tyres are wider than the aluminium desert wheels. The panels will fit over the fronts apparently, “but if we put it on, Andy won’t be able to turn the steering”, Mark tells me.

He needs to be able to turn the steering because there are bets riding on it. The turning circle is predictably rubbish, but Andy reckons he can make the turn at the end of Newquay Airport’s runway to bring the car back round. A turnaround crew is on standby with a Volvo and tow ropes in case he doesn’t make it. Because they’re not just shaking the car down here, but the whole crew. The rules of the Land Speed Record state that the car must make the run in both directions with no more than an hour between the finish of one run and setting out on the next. The team need to be well drilled, so preparing for every eventuality is good practice, and the lessons they learn here will be transferred out to the South African desert.

The rules of the Land Speed Record state that the car must make the run in both directions with no more than an hour between the finish of one run and setting out on the next. The team need to be well drilled.

We head over to the portacabin for the morning briefing. The atmosphere inside is what I imagine it must have been like during World War Two: clipped accents, precise instructions, matter-of-fact discussions about ignition, reheat and so on, plus conversation that includes phrases such as ‘fifteen-hundred-hours’ and ‘delta four’. And all taking place in a damp corner of a windswept airfield. Baggy overalls and a handful of moustaches complete the picture.

But what emerges is a very detailed and astute plan that, when it’s all boiled down, involves Bloodhound making two runs along Newquay’s runway. The complications are extensive, from commercial flights to having the right fire extinguishers in the right locations. When everyone files out I wait behind because I want to talk to Ron Ayers. Ron is the aerodynamicist who designed Thrust SSC and is now working on Bloodhound. I don’t think he’d mind me pointing out that he’s the most senior member of the team. I ask him if he’s ever thought of retiring. “I’ve been retired for the last 40 years, it makes no difference”, he tells me.

Ron’s background was as an aircraft designer before getting involved with Richard Noble on Thrust SSC. I ask him what the difference between the two projects are. “The one thing, perhaps the only thing, that never went wrong with Thrust was the engines, two ancient [Rolls-Royce] Speys we got out of a scrapheap. The thrust balance between them was perfect. That was the first car I’d ever designed. The fact it was a supersonic one probably wasn’t the best idea, but as far as I’m concerned both Thrust and Bloodhound are very low flying aeroplanes. They have all the same characteristics, the same safety features, the same culture as to how we operate. And we started off knowing what wouldn’t work – and two jet engines were never going to get us to 1,000mph.”

The car is due to roll out of the shed at 12.30, but I want to get Andy Green’s take on how Bloodhound compares to Thrust SSC before he has to don his steely stare. “I had a picture of Thrust SSC in my mind, which even towards the end still handled a bit like a high speed over-powered barge on occasion. Put simply, it was a research platform to prove it was possible to get supersonic, and then to set that supersonic record. But it was very much an aerospace scale of product forced in to a racing car role. And it did OK. But the steering was a bit vague, the brake feel was pretty much non existent, the power control was previous generation, with rods and cables linking the throttle pedal back to the jet engine…”

Bloodhound is a very different and more thoroughly engineered car. “It was more reliable on the first day of testing than Thrust SSC was on the last day we ran it”, Green says.

Bloodhound is towed out of the hanger at walking pace. To make the turn towards the main runway over half a mile distant, it has to be jacked up and the rear wheels placed on dollys to trundle the back end round. It’s a slow laborious process, because jacking up the rear means dropping the nose and they can’t have that scraping the tarmac. There’s a lot of waiting around: Andy makes notes, radios crackle and squawk, the jet’s starter is wheeled into position. It all serves to build anticipation. Because what happens when Bloodhound gets the all clear is nothing short of astonishing.

I’m standing a couple of hundred yards away, so there’s a delay. I see the jetwash increase, the heat haze trailing out behind the car as it starts to inch forward. Then the noise hits me, a proper wall of sound, massively loud and intimidating. It’s the familiar roar of a jet fighter as you might hear on the news or in a movie, but amplified. And it’s strange because it’s not coming from something with wings. Bloodhound looks small at this range, but the noise is huge, vibrating the air.

And then there’s a distant orange glow and it just zaps forwards. The rate of acceleration is astonishing because it reverses what we’re used to: a car that goes off the line fast and then gradually slows. Bloodhound just starts going faster and faster and my brain tells me that’s wrong, and then I notice the rate of acceleration, the distance it’s covering. No wonder Andy had a moment when he lifted off and still had a second of ramping acceleration to endure. I’d have been mashing the brake pedal in a flat panic.

He doesn’t make it round the corner at the far end without assistance, but there’s no panic, the team diligently goes to work, and a few minutes later Bloodhound is back with us. Negotiations are made with Newquay control tower and Bloodhound is permitted another run. Where first time round it had used the last two-thirds of the runway, this time it’s got the whole lot. What this means is that the show is over before Bloodhound even reaches us, stood halfway along.

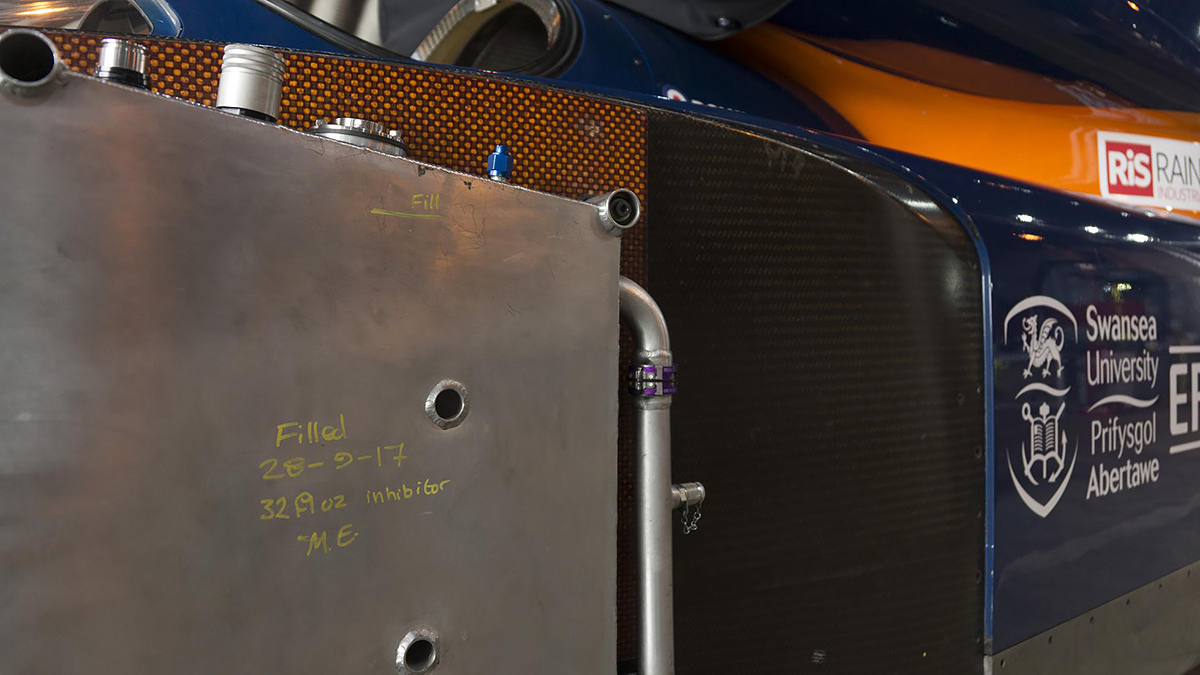

No matter, seeing it once was enough to seal it in my memory. And then the chase team turns up. Engineer Mark Elvin is beside himself – they’d turned round and were heading up the far side of the runway as Bloodhound started its run. It then came past them fully lit. Their faces tell the story. A radiant glow of adrenaline, excitement and unbridled joy at seeing their baby do what it is designed to do.

Much later and we’re in the portacabin for that evening debrief. The mood is still elated. Serious points are made. The fuel metering is slightly off, they’ll use a different Volvo for towing from now on – one that has its battery in the boot - and there’s a receive problem for Andy’s radio in the car. But it’s been another successful day. “What an incredible car” Andy Green tells the assembly, and there are nods all round. They’re off into Newquay for a curry tonight, back to kip in a barracks, then here again tomorrow to continue making Bloodhound the best it can be. Go and watch it run at Newquay on the 28th October. It’s not something you’ll forget.