In 2019, Pagani turned 20. And let a Pagani virgin drive Horacio’s own Zonda and the Huayra Roadster

Overtaken by a burgundy Citroen Xsara Picasso. The shame.

The brutal cringe-gland-rupturing humiliation of it. This is Horacio Pagani’s actual, personal Zonda: chassis no.6, the very car that graced the 2000 Geneva motor show stand – the first supercar ever to have a clear-coated carbon fibre body. And I’ve just allowed a claret French minibus to overhaul it not five miles from its birthplace. The happiest man in Modena trundles off ahead.

Words: Ollie Kew / Photography: Phillipp Rupprecht

Slouching alongside, Pagani’s factory test driver is aghast. Andrea’s one of those soul-crushingly handsome blokes who could’ve made it as a Gucci model or attacking midfielder for Juventus if he hadn’t been so inconveniently handy at driving. He looks up from his bored slump in the Zonda’s passenger seat, where he’s been idly WhatsApping his mates.

Record-scratch. Allow me to freeze-frame the moment. It’s a roasting day in mid-Italy. My right-hand, still a tad crinkled from where Horacio Pagani himself shook it earlier while mumbling “You be careful with my car, please” is now strangling the gearlever of an irreplaceable nugget of Italian supercar history, insured for five million Euros. The chap flanking me, now busily rattling though Modenese Tinder, is employed to set up Paganis.

And here I am, the oik who stood weak-kneed and gawping at a yellow Zonda S Roadster at the 2006 British motor show until my Kodak instant camera ran out of film, never thinking he’d even get to sit in the steampunk spaceship cockpit of a Pagani, now being instructed to pin it down a Maranello B-road to restore honour to hypercar royalty. I love this job, but sometimes, I have to tell you, I am completely out of my depth.

He’s a tricky man to read, eyes concealed behind mirrored Aviators reflecting my abashed, sweaty mug. “No, no, we not have this”, he spits, gesturing unkindly at the escaping familywagon. “Ees okay, just go fast, ees okay.” The hand not cradling his excitable iPhone nonchalantly points out the windscreen, over the Zonda’s mountainous front arches.

About an hour ago, I’d have kegged Senor Pagani and snatched his keys if it had made this preposterous situation look even moderately possible. The insurance computer had said no. I’d busied myself haranguing snapper Phillip around Pagani’s in-factory museum and unusually tasteful gift shop. But a man can only take so many pictures of leather toilet door handles, carbon fibre floor tiles and titanium door hinges (I’ve only made one of those up) for so long. Eventually, the Italians give a semi-official shrug of approval and I’m not waiting for a second opinion.

Before I’m allowed to drive, Andrea asks me to ride shotgun while he gently warms up the Zonda. By powersliding it out of the car park. “We avv to be careful, they no make-a these tyres any more. These are old tyres.” No kidding.

A supercar with 17-inch rims – the early Zonda really is from a different era. And now most of its rear tyres have been left behind on the forecourt.

I’d come to Italy for a day of days with Pagani because, believe it or not, this household name turned twenty in 2019. The first Zonda – a by modern standards plain 6.0-litre version – was revealed at the 1999 Geneva motor show.

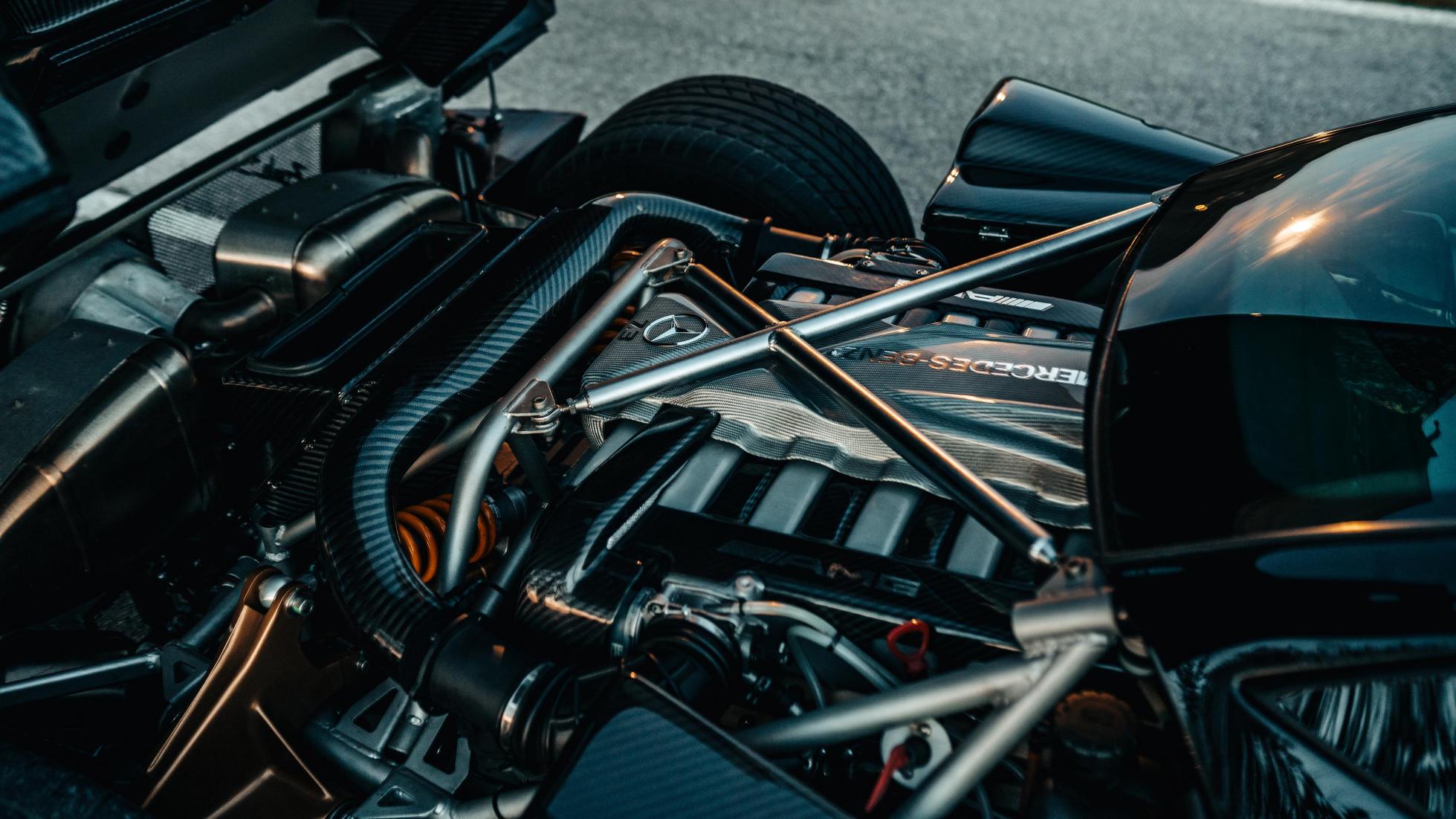

Its AMG V12 swelled to 7.0 then 7.3 litres, leading to the Zonda S, the Roadster, the Zonda F, the Cinque, and from thereon out it was bonkers one-off commissions and Faberge eggs on the mood board. Lewis Hamilton bought one. In purple. The slick-shod Zonda R set a Nürburgring lap record before it was cool. The Zonda basically became a legend in its own lifetime… and then a meme. The last one ever – one of three 760bhp chopped-screen Barchettas, complete with tartan seats – rotates on a plinth in the factory atrium. It’s Horacio’s. The other two went for £12million. Each.

I’d have liked chassis no.1, of course. Sadly, a victim of crash testing. So were chassis 2-4, though the carbon tubs survived and have gone on to birth ‘new’ Zondas. 005 was the first Geneva show star, and this clear-coat carbon example – a world-first by Pagani that was pure alchemy in the late Nineties – is chassis 006. Like almost all Zondas, it’s been mucked about with. The engine is the earlier 6.0-litre, officially good for 552bhp but probably chucking out more. The inboard suspension is from the Zonda F. And so, as everyone within a forty-mile radius will attest, is the titanium exhaust.

So, it’s not the fastest Zonda, or the most advanced. It doesn’t generate enough downforce to drive on an oligarch’s dining room celling and the seats aren’t upholstered in unicorn foreskin. Well, could be. The cream leather and suede are bobbly with patina. Good ol’ Horacio. This thing gets driven. He cares for it, but he’s not precious about it.

Andrea says he’ll go fast, so I can concentrate on not lunching the gearbox or knocking the intricate wingmirrors off, without feeling the need to wring it out. Keen followers of the story to this point will note this was, in hindsight, a lie.

He obliges. Good lord. This might be the small-engined Zonda but it flies, and the V12’s banshee shriek is transcendent. The power wars weren’t the right way to go. I’d rather have half the horsepower and this masterpiece of sound. After a few runs, Andrea bolts into a lay-by.

“Okay, now you go.”

His phone appears from his skinny jeans as he settles into the passenger seat.

Traditionally, I should say at this point that there was nothing to worry about; the Zonda’s a total pussycat, nothing intimidating about it, tally-ho and back home in time for tiramisu. That would be also be a lie.

It’s not the fastest Zonda, or the most advanced. It doesn’t generate enough downforce to drive on an oligarch’s dining room celling and the seats aren’t upholstered in unicorn foreskin.

The clutch is heavy. Feels like every prod might bend the delicate stem into the footwell. The gearbox in this example is a bit tired, and grrrrraunches into first. The door mirror pods look superb floating high up on the windscreen pillars, but they don’t reveal anything useful about where the back of the car is, or what’s behind it. What’s behind is significantly girthier than what’s up front. It’s like driving a Dorito. As a result, I’m bumping over cat’s-eyes and just about finessing my shifts when the marauding Citroen mugs me on the left. Never saw him coming.

Andrea gives me the hurry-up. I nurse a short-shift into third, reel in the maroon interloper and steal back past. Imagining how good that must’ve looked – and sounded – from the other vantage point of an old MPV gives me my first grin in the Zonda. I relax and start to marvel at how direct and beautifully communicative the steering is, at how expertly this preposterous Vegas cabaret of a car flits between corners.

Back in the day, I’d always assumed reviewers of Zondas were using adjectives as filler to pour into the cracks of reality. They were too busy being bowled over by the toggle switches and the shoes from the Pope’s cobbler to admit it was a tad shonky. Well, they were all right. The Zonda is a stellar sports car. It handles and rides and stops and then it goes and goes and sings. It is the best car I’ve ever driven.

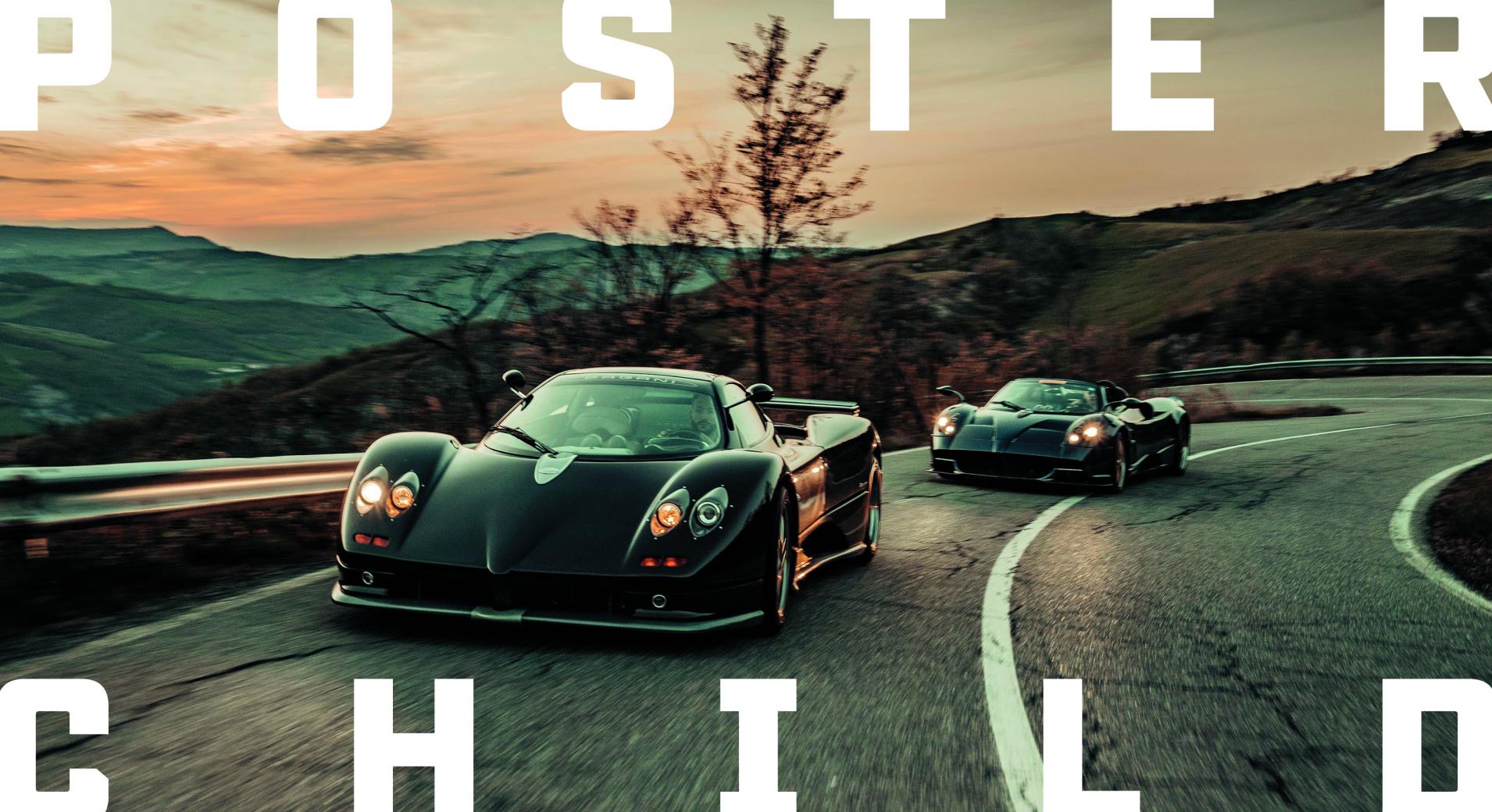

It is also the best Pagani I’ve driven today. Funny sort of day, really. The roads around the factory are quiet enough to let me dabble in the fabled work of the Italian supercar test driver, but they’re not a photogenic stage for the Zonda to meet the Pagani currently finishing its own production run: the £2.3million, 753bhp Huayra Roadster. So, in the cool of the afternoon, we head for the SP26 south of Maranello, where the road is twisty and bumpy and layered with ex-Pirelli. When Ferrari needs to sign off the next LaFandango away from Fiorano, they come here. This is the Bethlehem of supercar country.

The locals are understanding. They wait patiently as I execute six-point turns in the Huayra, marooned in the road while its seven-speed automated manual gearbox does the sums, before I’m spirited away in a bubble of turbo whoosh and clutch stink. They wave the Zonda by as Andrea arrives (late), with a broken headlight. We block the road entirely while snapper Philipp goes gooey over the honeyglow sunset. They politely turn off their engines, take photos on their phones, and gesture for us to take our time.

Imagine creating a £10m roadblock in Britain just to take some photographs. There’d be a class riot. Here, as the sun sinks below the hills and the Paganis tick and ping themselves cool, there’s just reverence. So long as the delayed folks can fondle the leather engine clamshell straps and score a selfie with the trademark quad exhaust, they’re satisfied.

Funny how the Zonda used to be the caricature supercar, and here, now, next to the Huayra Roadster, it’s almost slab-sided and gorgeously simple. It’s less intricate. Doesn’t look like you could break bits of it off if you leant on it. And it has menace, where the Huayra has art. Horacio explains later that the Huayra’s shape and details are ideas he wanted for the Zonda but the material technology simply wasn’t up to the job at the time.

Time was always going to be kinder to the Zonda, though. The original. Carbon tub, atmospheric V12, manual ‘box. The McLaren F1 Gordon Murray would have designed if he’d been at the ‘shrooms. In the decade Ferrari went F1-tech-doolally and Lamborghini boarded the Audi mothership, Pagani was the supercar cottage industry. It kept its innocence.

The Huayra was always going to struggle to replace it, and life was made harder by not being as pretty, or sounding anything like as special, and having a name half the world mangles. Weirdly, it’s the trickier car to drive. Terrifyingly, vividly fast. The single-clutch paddleshift gearbox is racecar brutal and doesn’t like to dawdle, turbo-lag is savage and it’s very, very firm. It feels every inch the machine built to do 200 miles an hour, but doesn’t tingle and gratify like the perfectly weighted Zonda does at 20. Love those aero flaps, though. Who wouldn’t be seduced by a car with ‘control surfaces’?

What it helped Pagani do was make the transition from being another supercar outfit to a billionaire’s atelier. Each one is so bespoke, when it’s sold on most buyers ship it back to the factory, have it stripped to the tub and start again. Only the chassis number stays original.

And it’s doing the business. The 800bhp Huayra BC Roadster is sold out. In 2021, there’s a new twin-turbo V12 supercar to come, and in 2024, an electric hypercar Horacio’s customers (and test driver) are begging him not to make. But he refuses to stand still. He can’t abide the idea of Pagani being overtaken. I know how he feels.