You join me mid-spin aboard Alain Prost’s 1983 Renault RE40 Formula One car. As yet, I haven’t worked out exactly what went wrong, but, to be honest, analysis of what caused me to be pirouetting down a hill on the Dijon-Prenois race track is not high on my priority list right now. Don’t stall, don’t stall.

Stalling would be ignominious. They’d have to send a crew out to restart me on the circuit. Some Frenchmen would shake their heads and wonder why on earth they’d let me drive this priceless slice of their racing history in the first place. I already know they’ll have heard. In fact, I suspect old men playing boules three villages away will have heard. An old turbo F1 car can’t be criticised for its lack of noise, and tyres this wide do not slide quietly.

Sitting so far into the pointy end, by the time the information had reached me that all was not well at the blunt end, it was too late to do anything about it. We were revolving. As far as it’s possible to have a good spin, I had a good spin. I remember being slightly alarmed at how rear-biased the weight felt, and all those earlier thoughts of irritated mechanics and village squares pausing while old men cup hands to their ears flashed through as well. But then, 360 degrees later, we were back straight, the engine was still running and – without even coming to a standstill – I was into first gear and away.

First gear, I realised as I eased back to the pits, was what had caused me the bother in the first place. My downshift from fourth into what I imagined was third, but I fear was probably first, had locked the back wheels. They weren’t wrong about the gearbox.

I come to a rest in the pits with the polished flat spots upright on the front wheels. Men are grinning. Relief, I suspect, at seeing their baby in one piece.

I’d spun at the start of my second lap, and all I can remember of my first is that all moisture seemed to have evacuated my mouth and eyelids… and that all I knew of this circuit was that it was the location of one of the most famous dash-for-the-line battles in Formula One history, between the Ferrari of Gilles Villeneuve and René Arnoux’s Renault back in 1979. Epic, wheel-banging stuff.

What few remember is that neither won. Up front on that hot July day was Jean-Pierre Jabouille in another Renault RS10. It was the first F1 victory for a turbocharged car.

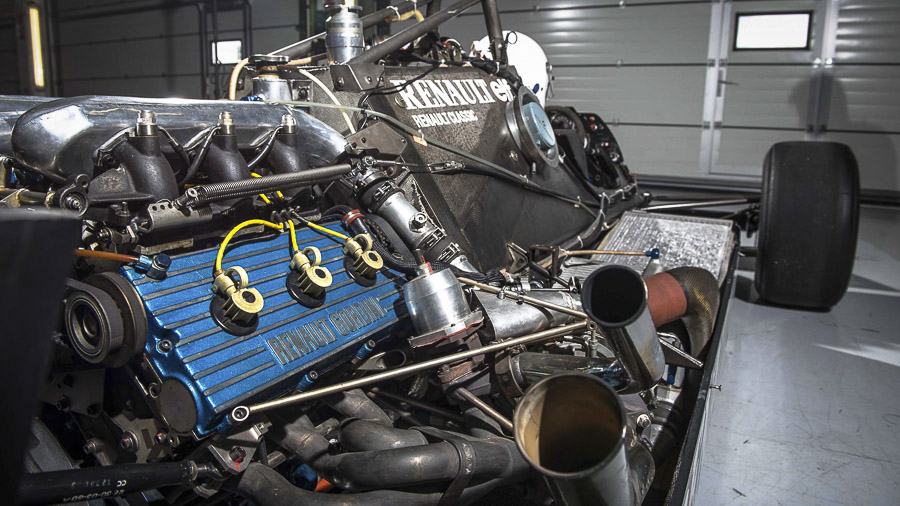

And now, at the same circuit some 35 years later, here I am in another. The RE40 was Renault’s 1983 F1 car, driven by Prost and Eddie Cheever. It is from the thick of the first turbo era, a 1.5-litre V6 that produced well over 1,000bhp in quali trim and around 750–800bhp in races.

It weighs 543kg. Even with 75kg of me on board, it has a power-to-weight ratio of 1,250bhp/tonne (a McLaren P1 is 650…) and a reputation for brutality that puts it on a par with Genghis Khan.

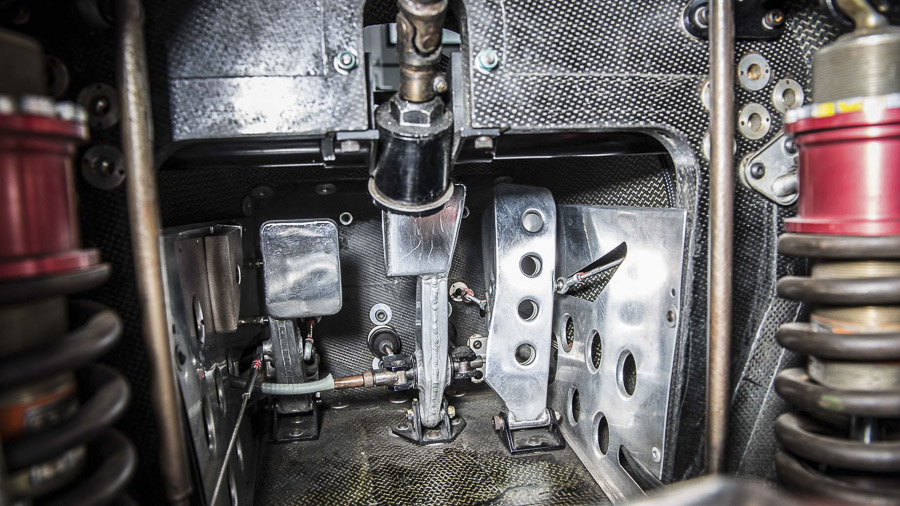

Boy, is it an intimidating thing to get into. You need the legs of a ballet dancer to thread down the footwell past canisters and bulkheads until your toes are squarely in the nosecone. It’s like sending your limbs caving. You sit high, you feel vulnerable, but you forget that because in front sits this fabulously shaggy steering wheel, behind it a rev-counter and down to the right a manual gearlever, five-speed, dog-leg first. So simple, so plain.

The widescreen vision of my helmet perfectly frames the front wheels, tiny mirrors, spoiler and nosecone. If I feel like I’m strapped to the front of a rocket, it’s because I am. It’s time to ride the lightning. For the second time, an engineer nods at me, I flick the ignition switch, give the throttle a centimetre and wait for the frantic squealing of the pneumatic starter. Pheeeeeeee-ooo. This time, it starts easily. Last time, it looked like this might all be over before it began.

You feel rather than hear the sudden flare of revs, but the vibrations through the carbon chassis aren’t too coarse. Unless you let the revs fade, at which point the engine will seem to drop a cylinder and lump about and will need a good dose of throttle to pull itself out of this lethargy. And yes, a good dose of throttle will have alarming affects if applied once you have anywhere north of 4,000rpm on the dial. And yes, 4,000rpm is where the dial starts.

What’s it like to drive? After three more laps, I’m starting to get the hang of it. Wonderful. Light. Hyper-accurate. Fast. Friendly. Dazzling. And yes, a bit savage. It makes me holler into my helmet when I accelerate, yet it drives with finger-tippy finesse you’d imagine would be at odds with the Thor’s hammer power delivery. It’s like a different car at either end yet somehow all gels perfectly together into something that’s both sharp yet supple.

Intimidation and fear fall from my shoulders, replaced by a breathless excitement, a love of the way this car changes direction, the trust you can put in those fat back tyres. Where’s the turbo lag I’d been afraid of? Not here. Renault had six years of turbo development by the time the RE40 appeared. Lag was a thing of the past. In its place, a wonderful mid-range drivability. There’s no surge because the revs build so quickly, as if the turbo can’t blow hard enough to keep up with the gear it’s in.

As a result, the RE40 doesn’t actually feel that fast. Odd though it sounds, I wanted this car to terrify me, to scare the bejesus out of me, to realise that the men who raced them were total heroes. Thinking about it, though, to race these cars, so exposed in the cockpits and with feet basically braced on the front wing, must have taken mighty cojones. For me, ultimately, I guess I wanted to sample it with the full whack of 1,200bhp, to be physically unable to get out of it afterwards.

But let’s not pretend it felt slow. It’s an amazingly magnanimous car to drive, and that makes it feel approachable and trustworthy, while the aero force at high speed sits you solidly into the tarmac. I later learn I hit 168mph on the pit straight, head bobbing in the vicious airstream. It felt more like 100. My favourite bit? The steep uphill exit of Parabolique, where second gear was freefall and third felt as if it would shoot you to the sky after the blind crest. Awesome.

So the trickiest part isn’t the power delivery, it’s the gearbox – the least forgiving component of the whole car. How long is the throw? Imagine cupping a pint glass, then imagine cupping a half. The difference in finger shape takes you from second to third. The distance between planes? Two fingers of your hand. Stay on a single plane and it was gorgeous, but just try to rediscover third from fourth…

It consumed gears – first, second, third, literally as fast as you could throw them through, it has double the power-to-weight ratio of a McLaren P1, yet it was easy to drive. How is that possible? Isn’t that the real achievement of these cars?

To give them little engines that don’t so much make power as detonate, and yet deliver a stable, manageable driving experience, one you’re always (almost always…) in control of and is able to slow down your perception of speed to the point you seem to have time to react. It’s not what I expected from this car, and, if I’m honest, it’s not what I hoped, but instead it’s something better – a realisation that, back then, they really knew how to build a racing car.

Be Safe, My Friend

By the time the RE40 came along in 1983, the most dangerous era of F1 was over. From an average of at least one racing death per year across the Fifties, Sixties and Seventies, there were only two during the whole of the Eighties – Gilles Villeneuve at Belgium in 1982, and Riccardo Paletti in Canada just a single month later (although both Patrick Depailler and Elio de Angelis lost their lives in testing accidents during the decade).

The two greatest dangers, fire and impact damage, had been reduced. The former by a move away from simple aluminium fuel tanks, to those with safety foam inside and a crushable structure surrounding them, while the introduction of carbon-fibre construction (the McLaren MP4/1 in 1981) instantly increased the rigidity of the driver’s safety cell.

But that’s not to say there haven’t been advances since. Compared with a modern F1 car, where you sit low and far back and the carbon fibre is designed to deform in a very particular way, the RE40 is primitive. Sticking the driver – a lightweight component – as far forward as possible was good car design. It enabled you to mount the heavy stuff – the engine, gearbox and mechanicals – as centrally as possible.

So, you do feel vulnerable – the exit from Parabolique, as the acceleration hits and your vision funnels, feels like being strapped to the nosecone of a Saturn V. In fact, it wasn’t until ’85 that frontal crash tests were introduced, and ’88 was the first year the driver’s feet had to sit behind the centre line of the front axle.

Two deaths on the same weekend in 1994, plus the tragedy of Jules Bianchi, show Formula One hasn’t perfected driver safety just yet, but think about where it’s come from.