The proposed shut-down of the Honda plant in Swindon will be a tragedy for the families of 3,500 workers. So too for the multiples of other people in the town and elsewhere that manufacture parts of the cars.

It would be easy to blame it solely on Brexit. After all, car makers loathe economic and trade uncertainty. And we’ve got a lot of that right now.

You have to hope that by 2021, the proposed shut-down date, things might be clearer. That date, by the way, signals the end of life for the current generation Civic.

However, whether we have a no-deal Brexit or a transition period, tariffs and extra paperwork will impose a huge extra burden on the car and component manufacturing industry. At the moment components cross the Channel freely, but that’ll change.

Ford’s European sales and marketing chief Roelant de Waard told me his firm estimates it will be €80 (RM369) per vehicle just in paperwork cost, for the components that cross and re-cross between the UK and the remaining EU. That’s before the actual tariffs which are expected to be many times more than that.

And de Waard says that currency changes since the Brexit referendum have already cost Ford €600 million (RM2.8b). For Honda, exporting cars rather than importing them as Ford does, a fall in Sterling is a lesser blow, but as components are bought in from around the world, Honda would still prefer stability.

However it isn’t just about Brexit. Another issue of trade has hit the plant’s chances. A new free-trade deal between Japan and the EU means that cars made in Japan now attract no tariffs coming into Europe. So there’s less motivation to build them in Europe. Honda’s plan is to draw production back towards its home. That’s a reversal of its old policy of “We build where we sell”.

But it goes deeper than that. Honda Europe has problems of its own, dating back to decisions made by its own Japanese HQ a decade ago.

In 2009, when the global financial crisis hit, Honda took a global view. Money was very tight and it decided to invest that money only where there was a chance of a fast return. Predictions were that that the US and Pacific economies would recover faster than Europe.

So Honda staunched investment in cars for Europe, figuring they wouldn’t get a quick return if they spent here.

The result was a range that became dated and gappy. Models such as a new generation of Jazz and the vital HR-V were launched here more than a year behind Japan. The dealers lost momentum. The customers lost interest.

So when, a few years ago, Honda presented its new range to Europe, not enough people noticed. The world had moved on. And now Honda is saying that Swindon is suffering because the world is moving towards electric cars.

Katsushi Inoue, Honda’s Chief for Europe, said; “In light of the unprecedented changes that are affecting our industry, it is vital that we accelerate our electrification strategy and restructure our global operations accordingly.”

Well, brilliant. Honda resisted making EVs while Nissan went ahead a decade ago. It will be a while before you can buy a Honda Urban EV, and it’ll be made in Japan. Even Honda’s first form of hybrid didn’t work well in Europe.

In 2009 Honda had a 1.7 per cent share of the European car market. It fell to 1.3 per cent the following year. By 2017 and 2018 it was down at 0.9 per cent.

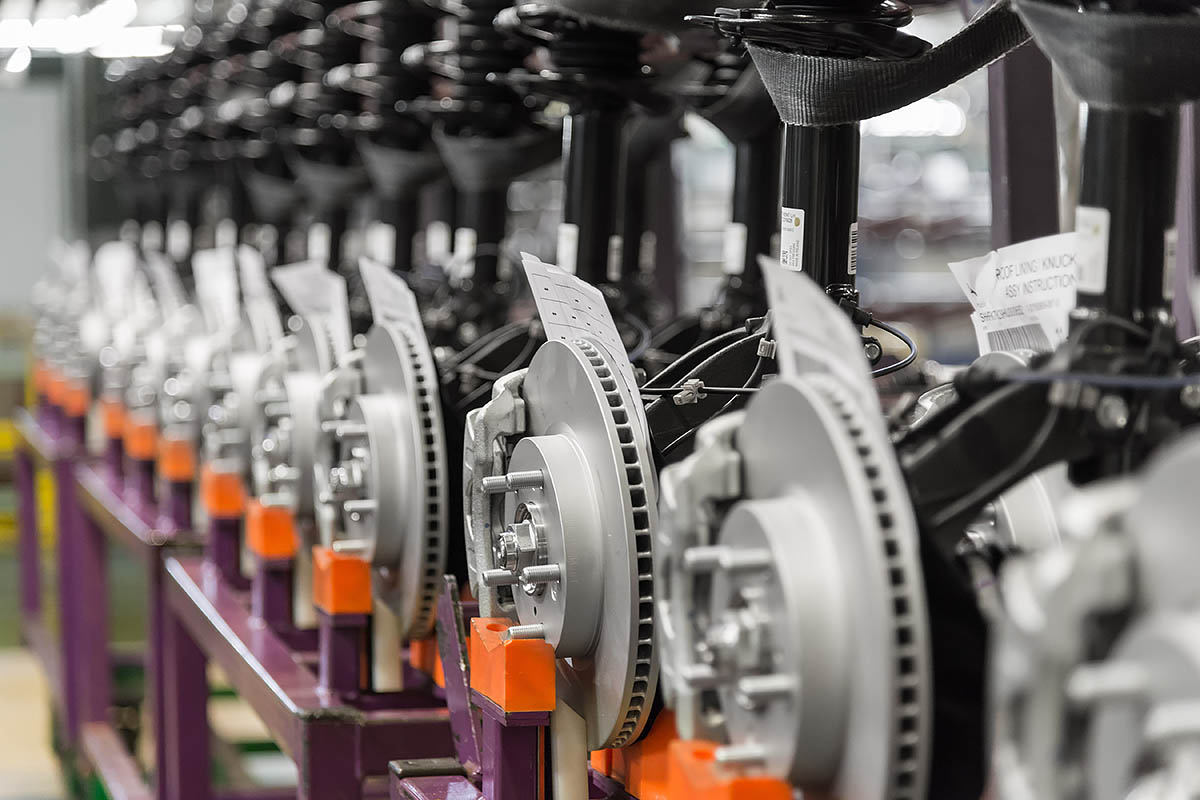

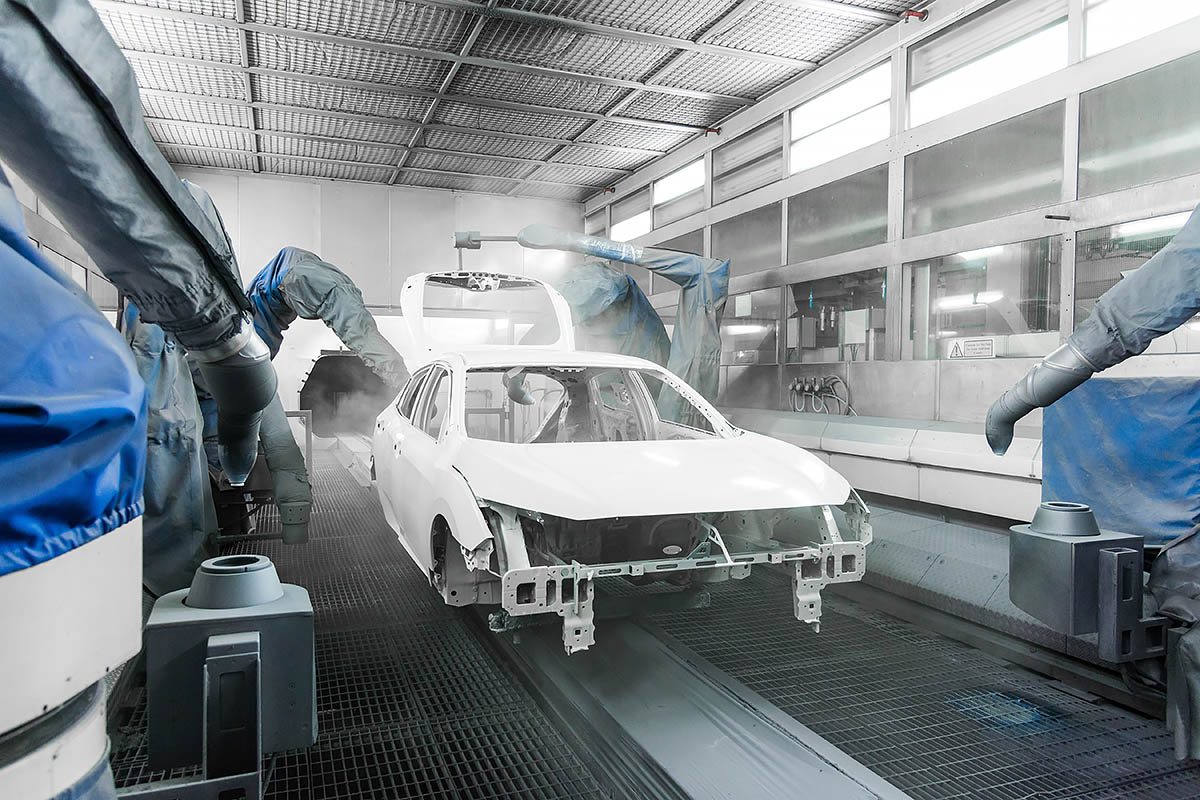

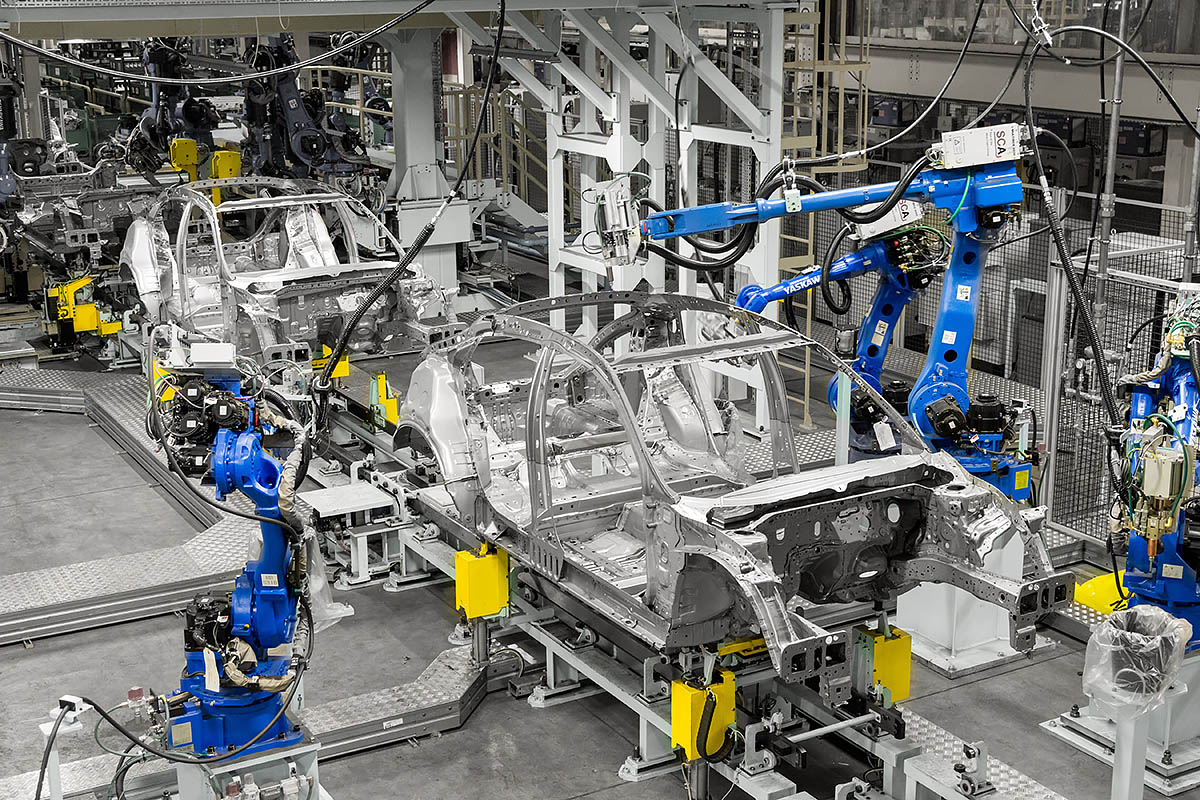

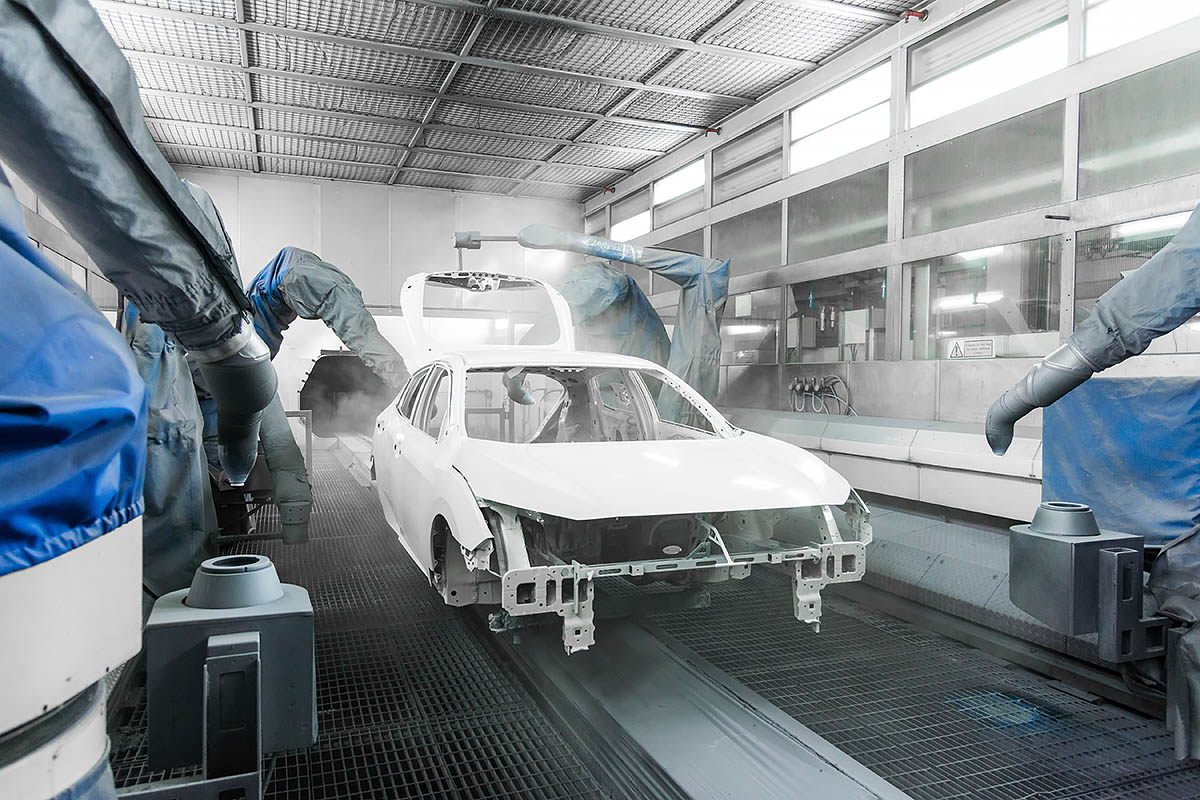

The Swindon plant was planned to build far more cars than it currently does. Its capacity is 250,000; it’s seldom made more than 150,000 a year. They’ve tried building CR-Vs and Jazzes there, as well as the Civic, and in the early days the Accord. So it’s a commendably flexible operation. Part of the flexibility comes from the fact it’s less automated than most other plants. And those workers build to a very high quality. The people of Swindon are not the problem. It was that the company has lost the knack of selling enough cars and had misread the market.

Honda can’t blame political forces. And I don’t suppose it will, because Honda has a policy of not making political pronouncements, and not accepting subsidies. Very different from Nissan or Jaguar Land Rover.

Nissan withdrew the next X-Trail from Sunderland. Well again, I don’t think that’s a vehicle that would have been a runaway success. The current one had few rivals when it was launched; the new one will have the very fine Skoda Kodiaq and Peugeot 5008 and VW Tiguan Allspace. Et cetera. That leaves less of a market for the X-Trail. The other Sunderland products, the Qashqai and Leaf, should be fine.

And as we noted a few weeks ago. Jaguar can’t just blame external forces for its current woes. It’s mostly about its chronic inability to sell XEs and XFs in significant numbers compared with German rivals.

If a factory sells cars that people want to buy, a headwind such as Brexit is an inconvenience. If the product’s not right for the market, it can be a killer blow.

- Paul Horrell