The shopping list to go drifting sounds simple; buy a ratty old rear-wheel-drive car, find somewhere safe to skid around, melt your tyres, do some crashing. And yes, for some grassroots sideways enthusiasts, that’s the deal. But when you climb up the ranks of drifting and get somewhere near the summit (Formula D, Driftmasters, D1GP, that kind of elevation) things get a little more technical. And scientific. And expensive. So we thought we’d do some invasive surgery and break down the build of a near 1,000bhp nitrous-fuelled championship-winning skid machine to show you just how potty these rolling bonfires are.

Be warned: things are about to get oily and nerdy. Very nerdy.

Now, let’s get the stereotypes and any ill-judged prejudice out the way first.

Because the drifting community is polluted by hats branded with energy drinks from the clearance shelf of Tesco, vape smoke and an overzealous online community, people often dismiss it as low rent. But in reality, the level of engineering in the cars as well as the precision and skill required with drivers is on par – if not above – other forms of top-tier motorsport. This BMW proves that theory.

It’s owned by professional Irishman James Deane, who also happens to be a rather dab hand at the old business of skids. Having started the art of ‘full-send’ in a ratty old Sierra aged 15 (remember the opening sentence of this story?) he won his first championship that year. And he hasn’t stopped winning since, now holding 16 national and international titles, making him the most successful drifter in the sport’s history.

Most of his shiny trophies were won behind the wheel of Nissan Silvias. But seeking a new challenge, James wanted a new car – something a bit more German and a bit more BMW-y. Luckily, there were some folks in Latvia who’d already done all the heavy-lifting in turning an M3 into a drifting demon: HGK Racing.

It may surprise you that a tiny company from a small country in the Baltics builds some of the most exquisite drift cars in the business. The level of fabrication HGK put in is well up there with any factory GT race car or WRC spec car. They’re the real deal. And there’s a lot of fabrication involved, with very little left of the original road car once they’ve got their grubby hands on it – only the head and taillights are the same. The build is so custom the only way to get your head around the scale is to do some invasive surgery and break each component down, piece-by-piece, so you can see the scale of what’s involved. So put your scrubs on, we’re going in.

Chassis

Even though the car looks like an angry M3, underneath it actually started out as something a lot humbler: an old BMW 320d. It shares all the same hardpoints as the M3, so it’s a cost-effective way of doing it as everything that’s not needed is chopped away and sold on.

When it comes to rules of the chassis in drifting there’s a lot of freedom: the chassis itself must be the same between the subframes, but you’re allowed to modify everything in front of the front subframe forward, and rear one back.

You can make everything from a tubular frame if you want. But James’ car runs the standard frame rails and floor pan. And before you think about going crazy and doing a mid-engined M3, that’s a no-no. You’re not allowed to modify the firewall. But other than that, the rules are very, very open: no restrictions on power, steering angles can be Black-Cab-on-Acid and the suspension points on the rear can be changed to maximise grip and minimise tyre wear.

Once HGK stripped the donor car down, fitted a cage, seam welded it up, threw a fuel cell in the rear and painted the chassis, it was shipped back to Ireland for James and his team to get busy with the juicy bit: the engine.

Engine

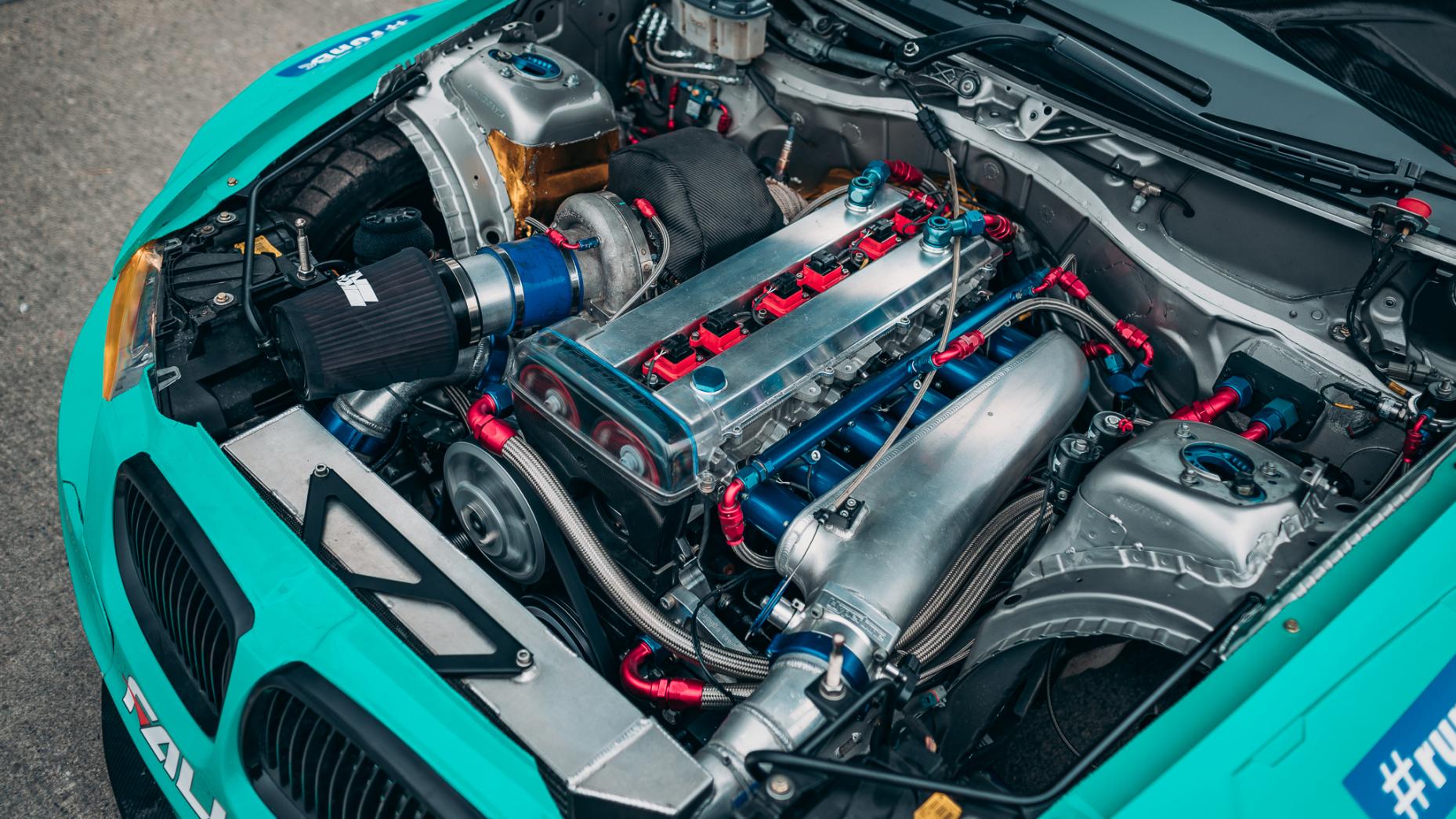

An E92 M3? Must be a V8 under the bonnet, right? Wrong. James has a habitual affiliation with Toyota’s tuners delight – the bulletproof 2JZ – so dropped an inline-six in after a bit of heart surgery… and heavy tinkering. See, this ain’t any 2JZ, but a custom-built motor from his company, Deane Motorsport. They buy the short block off Toyota brand new (yes, you can still do that even though the engine is as old as cassettes) then strip it back to get to the only bit of juicy meat they use, the standard Toyota crankshaft.

All the other bits are sold on, then Titan Motorsport solid steel billet main caps are put on as even though the Toytoya ones are pretty heavy duty and good for 750bhp, they have a tendency to fracture when you start juicing up the turbos, adding nitrous and all that other good stuff. This car has all that other good stuff. Then it’s outfitted with CP-Carrillo connecting rods, pistons with a 10:1 compression ratio (higher than you’d normally see, but the car runs on E85 race fuel so it’s perfectly happy), the standard steel Toyota head gasket is used but fitted with Brian Crower 280-degree camshafts, adjustable cam pulleys, 1mm oversized valves, dual valve springs and CNC port and polished cylinder heads. Gucci.

Turbo

Next up, a big ol’ snail is added. A BorgWarner EFR9180 to be precise. This is accompanied by Hypertune inlet manifolds from Australia, 45mm dual wastegates, Injector Dynamics injectors and a classy billet rocker cover. It’s a setup James and his team have got down to a fine art over the years and has proved to be a bulletproof wrecking ball of an engine, not having to put a spanner to it all season.

The 2JZ is not the golden bullet of drifting, though. In tandem drifting, you want to be within a gnat’s chap of your opponent, but with them braking and accelerating, that can be unpredictable. So an engine’s responsiveness is key but also has to have enough torque and power to keep those rear wheels smoking. Being turbocharged, the 2JZ has inherent lag. This is bad. So some run a stoker kit increasing the standard stroke from 86mm to 94mm, adding a load of low-end torque in the process… but also a lot more rotational mass potentially making it go pop. So that’s why you see other drift cars with big V8s and superchargers. But there’s something characterful to the 2JZ that James loves.

“Personally, I absolutely love the sound of turbochargers, wastegates hissing, parts banging – the 2JZ is exciting and makes it exciting to drive too. I have to get at it; work the pedals and keep the car in the right powerband which is all part of the fun. And with a standard crankshaft and 8,800rpm redline, it sounds pretty mighty for an inline-six, too.”

Nitrous

As mentioned, the 2JZ has one detrimental personality trait: lag. But James has one little trick up his sleeve. Or at the bottom of a bottle: nitrous. Yes, Hollywood’s favourite elements from the Periodic Table and a roadman’s favourite laughing gas has been equipped to take the fight to lag and increase the engine’s useable powerband. Nitrous kicks in at 3,500rpm to help wake the turbo up. Think of it like the turbo’s morning coffee. Or cocaine.

It’s controlled by the ECU and when James is over 85 per cent throttle and in positive boost pressure, the nitrous spools the turbo. Initially, it was just used between 3-5,000rpm. But then they got greedy (you’ve seen Fast & Furious, nitrous has that effect) so James has raised the cut out to 8,000rpm to increase peak power and torque. In Europe, he uses a 75bhp shot. But when competing in the US he doubles it to 150, which is quite a punch. Typically, a bottle in the US would last four laps, eight to 10 laps in Europe and takes power from 830bhp to around 1,000bhp. But they don’t really know for sure as it just keeps spinning its wheels on the dyno. In every gear. Yelp.

Carbon-Kevlar Bodywork

Under that toothpaste green and blue Falken livery lies the awesome greeny-gold reptilian weave of carbon-Kevlar panels. These are beneficial in two ways. One, they save an incredible amount of weight. The 3 Series isn’t a featherweight, so as much chonk needs to be lost as possible and these panels helped contribute to the 600kg diet. See the rear bumper? That weighs less than 1kg.

The second advantage is the strength of the panels. Even after a year of quite literally bashing around the world and a multitude of shunts, the E92 still wears its original panels. Fibreglass bumpers would explode on first impact, so teams used to carry a load of spares to each event. With the carbon-Kevlar panels, they’re so tough they just rebond or shape them if they clatter into something – saving a load of money. And HGK do all their own moulds, so they’re not widened overfenders and bumpers that tack onto the existing metal body. Oh no. Instead, every exterior panel bar the A, B and C pillars is reformed in carbon-Kevlar.

Suspension

As you can imagine, suspension set up is quite important when initiating a car to go heinously sideways. So there’s a suitably custom kit from Wisefab in Estonia (Eastern Europeans lurrrve to skid, see). It’s fully adjustable and has a monstrous 65 degrees of steering angle making it the easiest BMW to park in the world.

With regards to the geometry, James runs it with quite a lot of caster so the fronts self-centre quickly when penduluming from one drift to the other. There’s also a smidge of camber to keep as much tyre on the ground when at full-lock, plus a tiny bit of toe out at the front. These are all useful notes for your Mum’s next trip to the MOT centre.

The damping is also not the norm with the front being quite firm and rear hard. This is so when you lock the wheels courtesy of Mr Handbrake, the caster jacks the wheels up as you’re turning out, putting weight on the inside rear wheel which increases grip. The rear is soft to allow weight to transfer to the rear quickly to get as much forward and sideways grip as possible.

Brakes

Stopping power maybe isn’t something you’d put too high up on the list of priorities for a drift car, and you’d be right. Drifters don’t need the ultimate power of a circuit racer’s brakes (pads can last a few seasons in drifting) but pedal feel is very important. The stopper needs to be consistent as drivers constantly adjust the balance with their left foot.

But you may notice that there’s not one beefy Alcon caliper, but two. That’s for the hydraulic handbrake that gets pumped on and off (to avoid tyre flat spots) and lock the rear to initiate a drift or apply more angle. Two big brakes also makes it look pretty badass, right?

Cooling

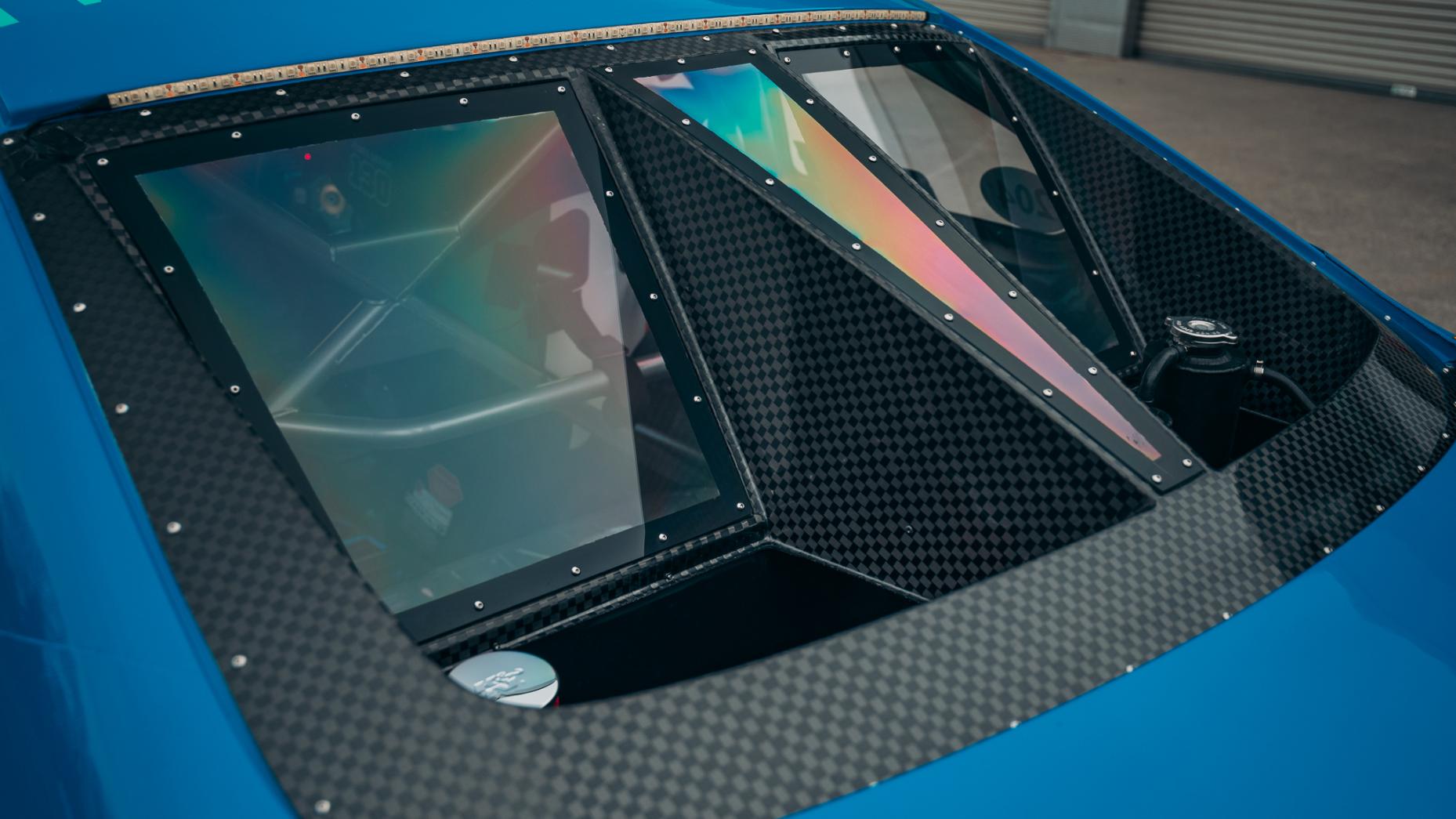

Only doing two laps of drifting for a total of 60-odd seconds, you may think you wouldn’t need crazy cooling. But there’s a lot of energy – and heat – produced when you have 900bhp at full chat and a custom made, thick aluminium radiator in the rear to feed. So there’s integrated ducting that not only looks awesome but rams air to where it’s needed.

Clever aerodynamic accoutrements in the bodywork direct the airflow effectively; like the tapered side skirts and vents to pull cool air onto the rear tyres and extract smoke out the back, the front bumper ducts that are angled outwards towards the back of the front wheels to provide tyre and brake cooling and that split rear screen that diverts cool air through the rear of the car and, in turn, the rear-mounted twin-core, dual-pass radiator and cooling system, before it exits out of two large nostrils where your shopping normally goes.

Wheels

Wheels are often seen as automotive jewellery, but in drifting there needs to be function to them too. Not only do they have to look good, the lighter they are the better. But there’s a fair amount of argy bargy in drifting, so they also need to be strong in order to withstand a bashing. So, if we’re butchering that jewellery analogy, these are knuckledusters.

Something you may not realise is the insane pressures drifters use. James runs his tyre pressures at the rear as low as 10psi (that’s sand driving levels of air) to increase the contact patch of the tyre but also keep the rear temperatures down. Just make sure the bead on the wheel is good enough that the flat tyre doesn’t come off the rim over a bump. It happens. And instantly makes you look like a bit of wally.

Tyres

Just because the purpose of drifting is to intentionally incinerate your rear tyres (James is judged on smoke produced, remember) you may think you’d want the crappest rubber possible. No-siree. Like circuit racing, you want a decent, reliable compound with grip. Yes, grip. And – given the livery – it may come as no surprise that the E92 is fitted with a Falken tyre. The RT615K.

It’s a semi-slick tyre that’s got stacks of forward grip to build up speed and get into the triple digits on the speedo to initiate a drift, with a compound that gives grip when sideways. This is important when you’re off-throttle, so the car doesn’t wash out and end up in the Armco. But the tyre also has to last. Well, a bit. It needs to be capable of withstanding abuse for two laps; a lead run, and chase run. If it can’t it’s useless – like going into an Olympic 100m finals in a pair of flip flops. Also, if the tyres are too soft, they’ll overheat and have no grip for the second run.

As consumables go, it’s at the top of the list. James will go through a set of tyres in 60 seconds. Which makes Chris Harris look like a saint.

Inside

Anything that wasn’t needed in the cabin was binned. So anything you see either serves a purpose for skids or make things safer. As you can see, the standard BMW dash has been ripped out and replaced by a lightweight composite variant. Any replacement panel that could be has been made from carbon; including the passenger footwell, door cards and pedal box. The roll cage, seats and harness are all FIA-grade to be able to protect James and his noggin if he has big shunt. Which he has in this car.

Last year, at the final round of Driftmasters Europe, James had the biggest crash of his 13-year drifting career when he aquaplaned at Mondello Park and speared straight into the wall. Luckily, because of all the precautions put in place (and because the E92 is a sturdy beast) both the car and driver were absolutely fine.

Balance

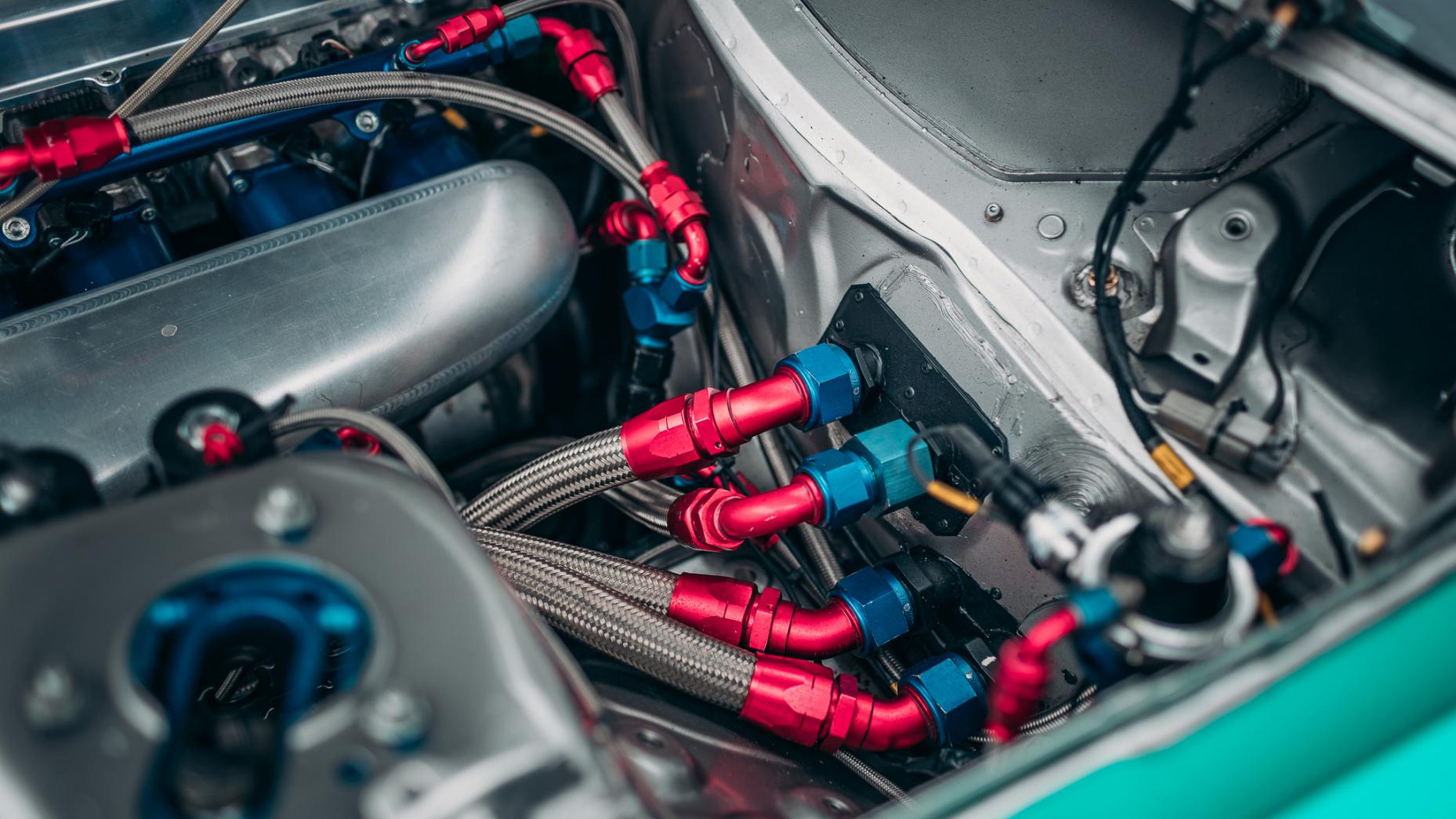

Being front-engined and rear-wheel-drive you’ll expect the weight balance to be biased towards the nose of the car, right? Wrong. James’ Bimmer has as 48:52 weight distribution to get as much weight over the rear wheels to improve forward momentum and grip to make sure he can do the fastest skids possible. So anything heavy that could be put in the back was. So the fuel tank, radiator, dry-sump system, oil-cooler, and battery were all chucked in the back.

The wheelbase also has a massive varying factor in changing the way a car feels on the limit. Cars with a shorter wheelbase like a Mazda RX-7 (a 95-inch wheelbase, if you’re keeping notes) will transition insanely fast, making it snappy and putting the driver on edge as they’re always thinking one-step about what it’ll do as it can get a bit fighty. Nissan Silvias have a 99-inch wheelbase, so are very forgiving and neutral but can be driven aggressively going from one big angle to another. But the BMW is a big old boy (roughly a 109-inch wheelbase), so James has to work the car a lot harder for it to change direction and get into a flowing run. It has its upsides though, as it’s slower to react, making it smooth and fluid and not require many corrections when it is going sideways.

Lines and hoses

Just like you want decent cholesterol-free veins to pump blood around your body, a race car needs good lines and hoses to pump all the fluids around the car efficiently. These braided lines and hoses are not only durable, but can snap on and off – making it easy to source problems and replace them if necessary. It also puts people’s OCD at ease, as the dry-sump lines, fuel lines, brake lines, coolant lines and any other lines are all nice and neat. See, you’re either someone who has wires coming out the back of your TV and Hi-Fi looking like Medusa’s bed hair, or you cable tie them and hide them behind the wall. James and his team are of the second school of thought. Tidy.

Cupholder

Who said race cars can’t be practical?! The Eurofighter even has a carbon cupholder and somewhere to store your iPhone. A Lamborghini Aventador has neither of these things, can’t skid half as well and costs twice the price.

Price

Now, you wouldn’t be the first person to have looked at old 3 Series classifieds with the intention to go and skid about. So how much does it cost to take an old 320d and turn it into a championship-winning drift car? Well, around £150-200k. Which, if you think about it, isn’t that bad. Yes, you can’t use it on the road, but the quality of the componentry and fabrication is some of the best in the biz. So when you think about what you’re getting for less than a used Lamborghini Huracan, it seems like a bit of a bargain. Well, that’s the argument you can use to your significant other when you’re justifying that you’ve bought a ratty old BMW to go and do some drifting.